Shadows of the Neon Wilderness

|

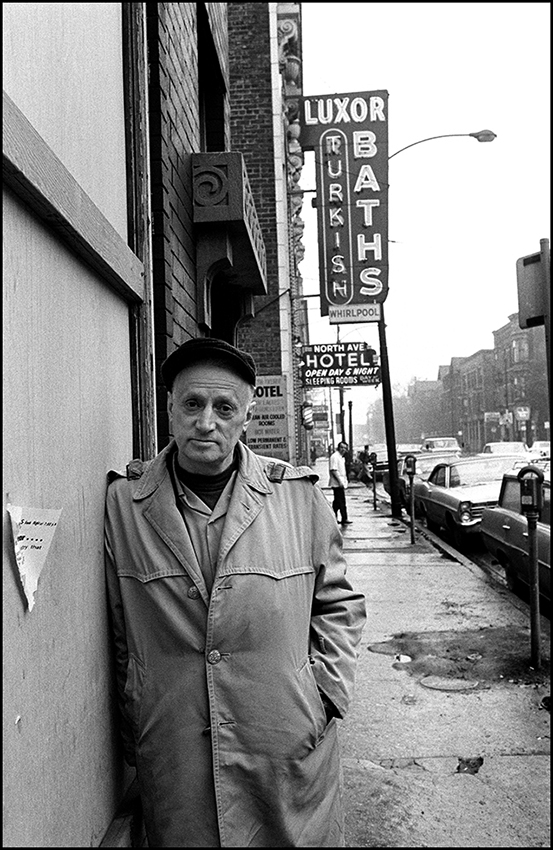

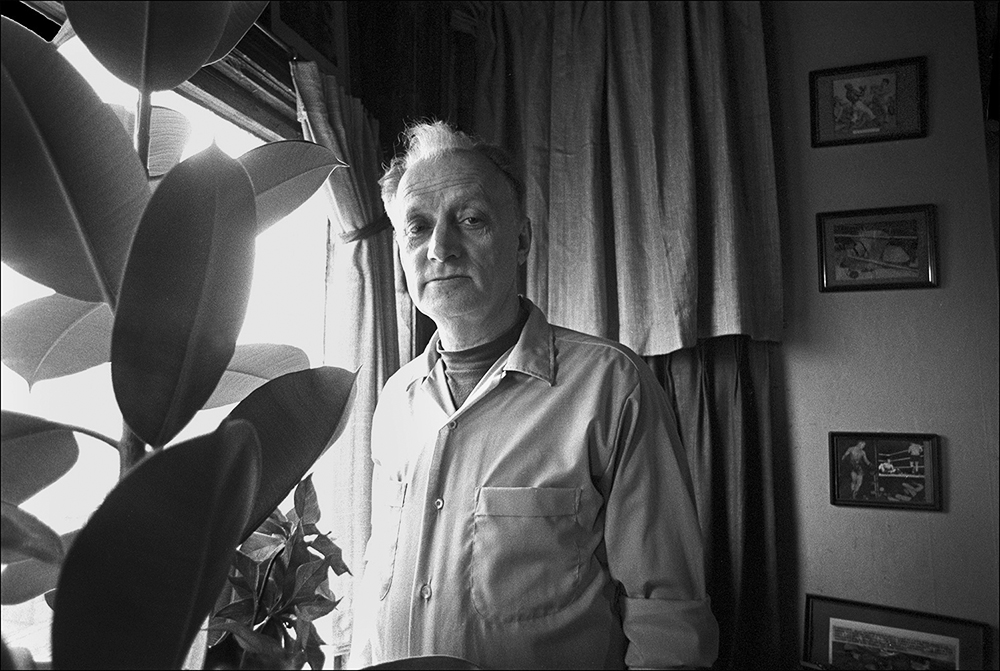

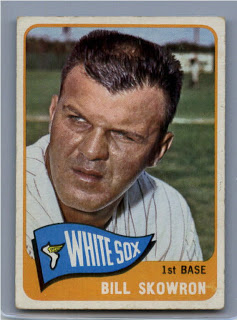

Early in his first term President Obama made noise about bringing back a new deal of the WPA (Works Progress Administration) as a method to resurrect the economy. It is too bad this never came to pass. Writers, artists, former newspaper journalists and photographers could chronicle the green economy, foodways and stories of the scores of immigrants who are changing America’s landscape. Engaging state travel guides were written between 1935 and 1943 through the Federal Writer’s Project of the WPA. I still use them today when I travel. The project provided a platform for emerging voices such as Saul Bellow, Studs Terkel, Eudora Weldy and Nelson Algren (1909-1981). In the late 1930s Algren was supervisor of the WPA Illinois office. His assignment was to gather information for a national “America Eats” program where he was to produce a series of regional guides descirbing immigration customs and settlements as they related to food. Algren honed his interviewing skills and surely learned the timeless power of food memory, which is a device I try to use in my conversations today. In 1992 the University of Iowa Press published his work in “America Eats,” where Algren wrote: “If each of all the races which have been subsited in the vast Middle West could contribute one dish to one great midwestern cauldron, it is certain that we’d have therein a most foreign and gigantic stew: the grains that the French took over from the Indians, and the breads that the English brought later, hotly spiced Italian dishes and subtly seasoned Spanish ones, the sweet Swedish soups and the sour Polish ones, and all the Old World arts brought to the preparing of American beefsteak and hot mince pie. Such a cauldron would contain more than many foods. It would be at once, a symbol of many lands and a melting pot for many people. Many peoples, yet one people, many lands, one land.” And many peoples will gather at 7 p.m. Nov. 22 at Lottie’s Pub, 1925 W. Cortland (at Winchester) to celebrate the 25th anniversary of the Nelson Algren Committee. The committee has helped keep Algren’s work and life alive and in the public eye since it was formed in the basement of Lottie’s. For decades Lottie’s basement was the home of all-night poker games which were financed in part by Algren. One time Algren played a poker game fueled by advance money for an unwritten book. He lost the advance in the game. Chicago theater veteran Donna Blue Lachman will be on hand as will former Saturday Night Live writer (1975) Nate Herman, who performed at the inaugural event. Archivist Tony Macaluso of WFMT will present rarely heard Terkel interviews with Algren and expect an appearance from historical re-enactor Paul Durcia. The group will also celebrate the upcoming release of “The End Is Nothing, the Road Is All,” the definitive documentary about Algren, which the committee helped produce. Co-creator Mark Blottner will be on hand to offer a sneak preview. Blottner’s documentary looks at Algren’s political views while the previously released Michael Caplan biopic “Algren” focused on Algren’s literary career. “The End Is Nothing, the Road Is All” is inscribed on Algren’s headstone in the Oakland Cemetery in Sag Harbor, N.Y. (John Steinbeck also lived in Sag Harbor from 1955 until his death in ’68). In his true independent style, Algren chose eternal words that were not his own. Great Plains novelist Willa Cather came up with the road quote. Committee co-founder Warren Leming will be on hand and he has worked as a liasion with Seven Stories Press to get Algren’s work reissued. Previously unpublished works like “America Eats” and “Nonconformity” are now available to the public. The committee celebration includes free pizza and a cash bar. Admission is just $10, $5 if you are a student, senior, cash strapped or all of the above. You can keep the ball rolliing at 7 p.m. Nov. 28 when Firecat Projects, 2124 N. Damen, welcomes storied Algren photographer Art Shay as he opens an exhibit of his documentary photographs of Algren in Chicago. Shay will give a talk and there will be ample beer from Three Floyds Brewing and wine from Red & White Wines. I was at the first Nelson Algren Committee event, Dec. 2, 1989 at Lottie’s and I’ll be at this one Talk about food? The 1989 event was catered old world Polish style by the late great Sophie Madej, owner of the Busy Bee Restaurant, which was under the El tracks just a couple blocks away from Algren’s home, 1958 W. Evergreen. The Busy Bee is one reason I moved into a graffiti-laden shooting gallery at 1501 N. Wicker Park in 1979. Food was always on Algren’s radar. One of his most popular lines comes from his 1956 novel “A Walk on the Wild Side,” (the template for the Lou Reed hit) where he wrote, “Never play cards with a man called Doc. Never eat at a place called Mom’s. Never sleep with a woman whose troubles are worse than your own.” Well, there was that one time I was playing cards with Doc at Mom’s and went home with the paroled waitress…… Proceeds from the $5 cover in 1989 that night were to be used to honor Algren with a work of art. The artwork or statue has never come to fruition. I loved Harry Caray, but if Chicago can have a statue of Harry Caray, there certainly should be a physical artistic tribute to Nelson Algren: A wrinkled face with rolled up sleeves. Former committee member Char Sandstrom advocated a memorial fountain to be dedicated to Algren at the “Polonia Triangle” park and subway stop at Division, Ashland and Milwaukee. The fountain with a plaque honoring Algren came to fruition in September, 1998 in a project by the Chicago Public Works Commission. The committee also worked with Chicago-based Seven Stories Press in promoting and re-issuing Algren’s books. Algren was born as Nelson Ahlgren Abraham in Detroit in 1909 and moved with his family to the south side of Chicago when he was three years old. His mother ran a candy store on the south side. Algren left Chicago in 1975. Through the early days of the committee I got to know founding member Stuart McCarrell. The Chicago playwright-electrical engineer died in 2001at age 77. Stuart was instrumental in getting a plaque in front of the Evergreen address. There is also a marker at the Evergreen site as part of the Chicago Tribute historical location project, sponsored by the Chicago Tribune Foundation. McCarrell and Algren were die hard White Sox fans. During the mid-1960s they would stop at Tufano’s Vernon Park Tap in Little Italy for a meal and a couple of glasses of tap beer before a game. The White Sox often would lose in their presence, which McCarrell said fit Algren’s under-dogged character. He had deep empathy for people oppressed by legal and political maneuvers. “The great thing about Nelson is that he was a gut radical,” McCarren told me on the eve of the committee’s first event in 1989. “He would pay $65 a month for this working class apartment on the third floor of 1958 [Evergreen]. He always acted, dressed and lived as a member of the proletariat. “Nelson was one of the first guests on [Sun-Times columnist Irv] Kupcinet’s program. What made it a good program was that Nelson represented the outsiders and the unknown point of view. He’d never dress up. Then, they’d say things like, ‘Mr. Algren, why is it you associate so much with that type of people?,’ meaning the poor and underclass. He’d say, ‘The strange thing is that I associate with people like you.’ He had a great empathy for the least of these.” Algren biographer Bettina Drew wrote, “The gates of his soul opened on the hell side.” Tributes will be paid to McCarrell and Algren friend Studs Terkel at Lottie’s. After Algren died of a heart attack, his body was taken unclaimed to Manhattan, about an hour north of his home. Studs was the first on the phone to get the body released. Algren remains fiercely relevant with the great divide between the haves and have-nots in contemporary American society. He saw the deep end of a similar polarization in the diners, restaurants and kitchens of at the end of the Depression. The long Midwest shadows of the late 1930s colored his words forever, just as the dry California fields influenced John Steinbeck. If he were alive today, Algren would have nothing to do with Chicago’s Michelin rated restaurants or fancy bars with $20 cocktails. He would have something to do with you. And he does. |

Leave a Response