The lost Bill Veeck files

Baseball Hall of Famer Bill Veeck thought outside the box.

One of the best ways to understand Veeck’s brilliant mind is to go inside a large plastic storage box of treasured clippings, notes, paperwork, and pictures covering Veeck’s years of owning the Chicago White Sox, Cleveland Indians, and St. Louis Browns.

It is a remarkable archive that has never been made public.

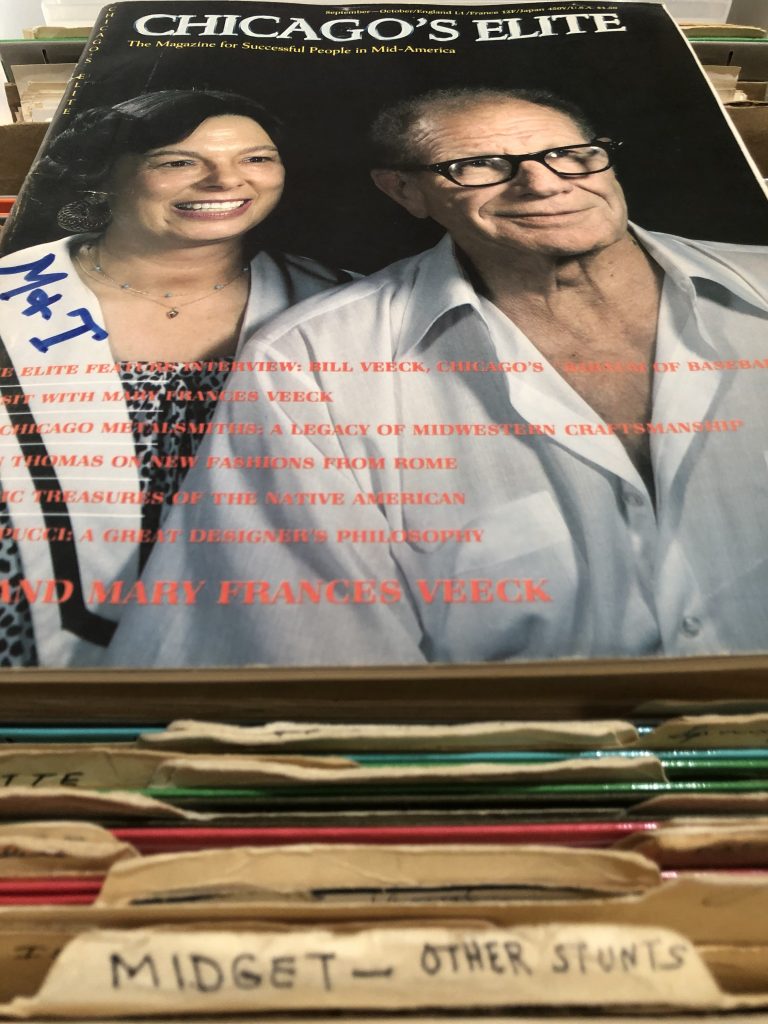

Mary Frances, Bill Veeck, and midget files.

There’s files and files and files: “How Veeck Got the Sox–1975.” “Scoreboard.” “Buys Browns 1951.” “Veeck-Cuba” “Disco Demolition.” “Amputation,” “Veeck in High School (Hinsdale Central). And maybe my favorite, “Midgets–Other Stunts.”

I found the Arthur Andersen & Co. White Sox financial statements from 1976 and 1977. (Cash on hand Dec. 1, 1977, was $350,000 in a note from White Sox treasurer Leo M. Breen.) I discovered a 1981 Chicago Reader cover profile on the late radical/grassroots organizer Saul Alinsky. Who saved that? Tom Ricketts wouldn’t have saved that. Reader correspondent Robert McClory wrote that Alinksy was “the major catalyst of the citizen participation movement in this county.”

Well, Veeck was all about fan participation.

Besides the box of history, there are also old 16 mm reels and 3/4” videotapes. One moldy, sealed film is canister addressed to Veeck and the St. Louis Browns. It appears to be an audition tape. Veeck bought the Browns in 1951. Other sidebars include daughter Marya Veeck’s 1970s oil portrait of her mother Mary Frances Veeck in their Chicago home. Mary Frances recently celebrated her 100th birthday.

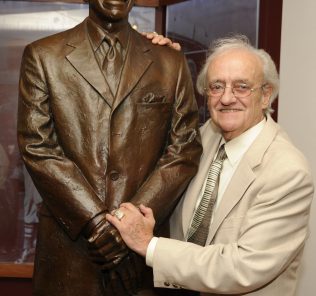

Former White Sox media and promotions coordinator Judy Shoemaker has kept the archives close to her heart since she left the team in 1981. That was the year Veeck sold the White Sox. He spent some of his retirement years in the Wrigley Field bleachers before he died in 1986. Veeck was inducted into the NationBaseball Hall of Fame in 1991.

His plaque reads, “A champion of the little guy.”

Shoemaker lives in Traverse City, Mi. and has spent much of the pandemic downsizing. It was time to allow the archives to move forward. Shoemaker contacted Marya Veeck. She lives on the north side of Chicago with her husband and their rescue beagle Quincy. Veeck owns and operates the August House art studio in Roscoe Village.

I recently stopped by the studio to look through the Veeck collection. I hadn’t been this excited since August 1990 when I sat next to Andy the Clown on the beer vendor bus trip to watch Frank Thomas make his major league debut at County Stadium in Milwaukee.

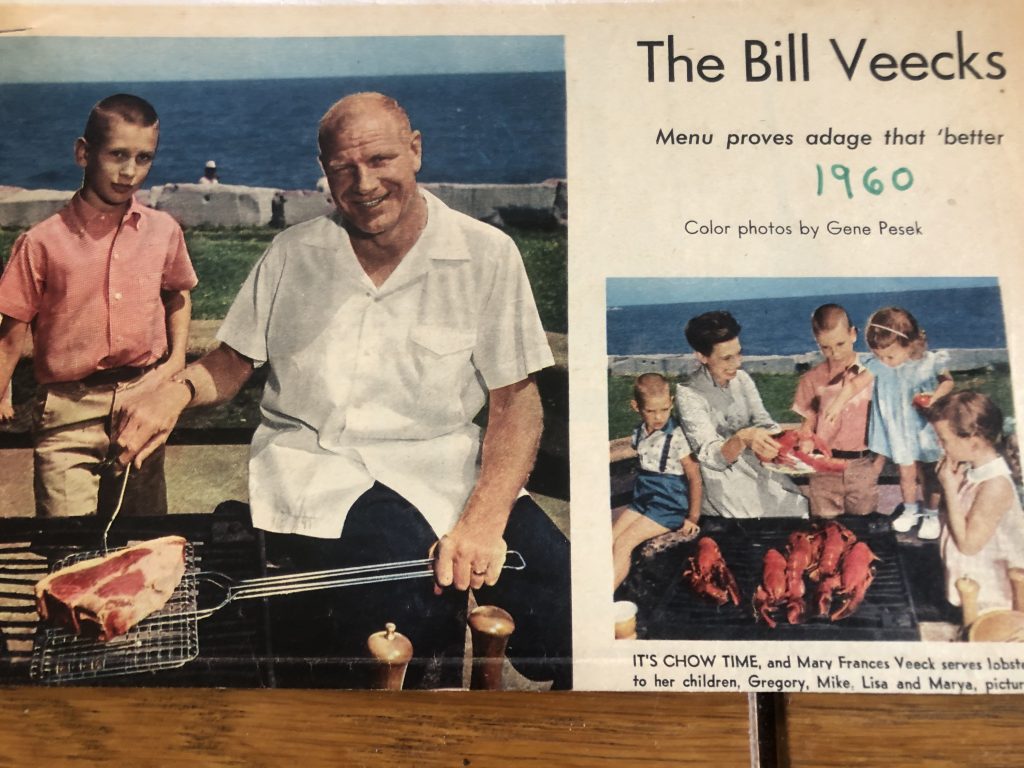

Mike and Bill Veeck cooking up another promotion (From the lost Veeck files).

The comprehensive nature of the collection can be attributed to long-time White Sox employee Don Unferth. The native of North Fon du Lac, Wis. began his 32-year run with the White Sox in 1948 as an assistant farm director.

Unferth was named publicity director and statistician in 1955 (Veeck also owned the White Sox 1958-61) and became traveling secretary in 1971.

Veeck returned him to the public relations department in 1976. Unferth retired in 1980 just before Veeck sold the team to Eddie Einhorn and Jerry Reinsdorf. Unferth died in 1989 at the age of 75.

There are ticket stubs, announcer’s tags, and Studs Terkel’s address handwritten on a 1980 Mailgram. I found a color photograph of Bill and Mary Frances sitting together in the Wrigley Field bleachers on opening day, 1985. Scrawled on the back is the note that it was Bill’s last opener and “Our last photograph together…”

The Veecks final opening day together. (From the lost Veeck files.)

“All of those clips and most of those files, particularly the 1950s and the Cleveland stuff, that’s all Unferth,” Shoemaker said. “Our operations group of promotion and ticket people reported to (Veeck’s loyal business associate) Rudie Schaffer. We had great fun. We knew the club was getting sold. There wasn’t going to be much of a notice given to the legacy of Bill and Rudie.

“Looking through Don’s files and seeing all that stuff, there was a moment between Rudie and our little gang of marauders where it was, ‘We’re going to liberate this!.’ We were sure it was going to get trashed. When Mr. Einhorn and Mr. Reinsdorf took over the last thing they wanted to be reminded of was anything to do with Bill Veeck. I know they got rid of a lot of stuff we didn’t liberate. We didn’t know what Bill was going to do but maybe Bill would rise again in some way and there would be the use of having all this history.”

At the time Shoemaker lived in a Bridgeport apartment close to the ballpark. “We just loaded up all that stuff into a truck and into my house,” she said. “There were a couple of other boxes of files Mike (Veeck, Bill’s son and promotions director) had, I’m not sure. I had no interest in working for the new owners so I went on my merry way. And that stuff stayed with me. For a long time.

“When Bill went into the hall of fame we discussed sending it to Cooperstown. But the hall said, ‘Until we see it, we don’t know if we want it. If you ship it, we’re not going to ship it back if we don’t want it.’ Okay. That didn’t work. So I hung onto it forever and ever. I didn’t know what to do. At one point there was going to be another book. Whoever would write a book, I had the stuff. Some of the things on the reels go back to Cleveland. When they were in Cleveland–ready for this?–they did ‘B.V. on T.V. for G.E.’ General Electric was a big sponsor of the Indians. I think some of that is on those film files.” Veeck owned the Indians from 1946 to 1949.

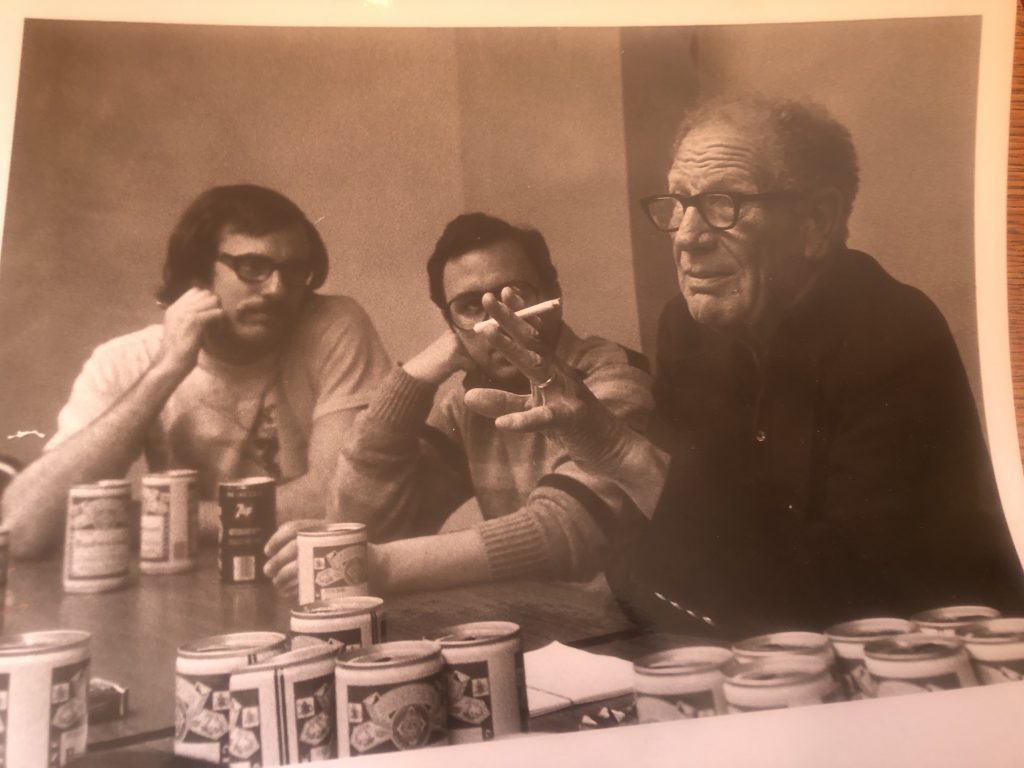

What a fun press conference! (From the lost Veeck files.)

I suggested the Veecks and Shoemaker should send materials to actor and Veeck friend Bill Murray to resurrect the idea of a Bill Veeck movie. We need something like that right now. In the lost box’s “Broadway Play–Veeck” file, there’s a 1978 item from Tribune columnist Maggie Daly that reported that Veeck would be portrayed by Darren McGavin (“Mickey Spillane’s Mike Hammer, “Murphy Brown,” etc.) and Mary Frances would be played by Nanette Fabray in the musical “Veeck,” that was being written by Neil Simon’s brother Danny.

I also found Bill Veeck’s un-dated hand-typed, edited, and personalized lyric sheet:

“A second-hand park; an overdue bill

That’s why they call me Secondhand Will

Even that young speedster in the garden

Was a throw-in in another bargain

Second- hand bats, second-hand balls

I never got an athlete for cash

Even our new slugger, who the fans all adore

Has got the bankers calling if he goes 0 for 4

Secondhand Will, Secondhand Will

From 35th and Shields.”

“Oh, he wrote that to the tune of (the Fanny Brice song from “Ziegfield Follies”) ‘Second Hand Rose’,” Shoemaker said with a tinge of joy in her voice. I found the telegram from American League

president L.S. Mac Phail, Jr. forfeiting the second game of the July 13, 1979 double-header to the Detroit Tigers after the Disco Demolition disturbance.

Shoemaker said she knew the files well but I stumped her with my Saul Alinksy discovery. “That would have come from Bill,” she said. “He was an activist. Bill may have been somehow involved with him (Veeck is not mentioned in the story.) When they were in Maryland, I know the stories of a parade of activist and civil rights people in and out of the Veeck household.”

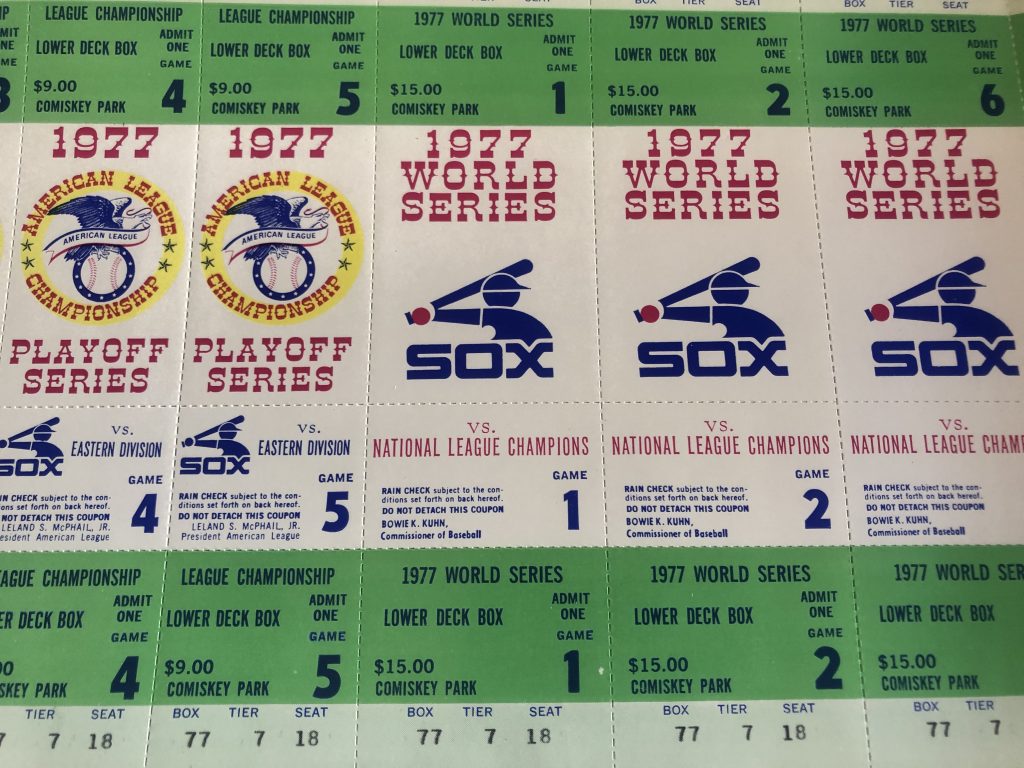

From “Midgets–other Stunts” I walked Shoemaker through the Feb. 2, 1977 proposed calendar of “key special events” for the White Sox 1977 season: “Farm & Garden Day,” “King and his Court,” “Mini State Fair,” (the always popular) “Beer Case Stacking” and “Mexican Rodeo Night” just to name a few. “We had cow milking contests,” Shoemaker said. “We were always parading animals around the warning track.”

I found a 1977 invitation from Lawrence Burkholder, the president of Goshen (Ind.) College inviting Veeck to speak at the school. “We are interested in the success of the White Sox,” he wrote in part, “(College board member) Art Decio speaks highly of you–your values, community spirit and moral courage and sensitivity. These in particular were the qualities which led our faculty committee to propose you as a lecturer.”

The South Side Hit Men never hit the postseason (From the lost Veeck files.)

Shoemaker insisted that I not make this story about her.

But in going through the archives, I wondered about women in the sports workplace during the 1970s. There was a clip from the Salinas (Ks.) News Journal about Veeck hiring Mary Shane in 1977 as major league baseball’s first woman broadcaster. Shane, 32, was paired up with Harry Caray, Jimmy Piersall and Loren Brown. “I remember her,” Shoemaker said. “She had to know it was not going to go well. But Bill was ahead of his time.”

I unearthed an Aug. 27, 1979 feature from Advertising Age where Veeck said, “There is absolutely no doubt in my mind that in the not so distant future, you will have women playing in the major leagues.” He added that he once tried to sign Babe Didrikson, who was playing second base for the House of David barnstorming team. Veeck got the tip from the Negro League legend Satchel Paige.

Veeck employed other women in the front office, including Millie Johnson, the long-time director of the White Sox ticket office. Johnson, who died in 1992, was Major League Baseball’s first female

ticket manager. “I coordinated all the radio and television broadcasts,” Shoemaker said. “Getting Harry Caray and Jimmy Piersall to do the right things at the right times, tell them where the commercials were. They were professionals, but you couldn’t be quite sure how it would go (laughs.)

“Bill used to sit in the back row of the press box. Me, being naive, I’d be in and out of the press box with notes. In my first season, I had something from one of the broadcasters and they said, ‘Take this over to Bill.’ So I went into the press box and got to the back row. He said to give it to Jimmy DeMaria who ran the messages on the scoreboard.

“I walked down two rows and gave it to Jimmy. (Chicago baseball columnist) Jerome Holtzman leaped out of his seat and bellowed, ‘Get out of the press box!’ at me. I was startled. No women in the press box. I had no idea. At the time there were no female writers. Then Bill stood up and said, ‘She works for me. She can be in the press box any time she wants.”

Veeck built bridges. He helped open the door to Shoemaker’s illustrious career in sports. After the White Sox she went on to become Vice-President, Marketing for NBA Properties in New York between 1988 and 1995 and between 1998 and 2003 Shoemaker was Director of Marketing and Promotion Services at the Salt Lake Organizing Committee for the Olympic Winter Games. “Quite frankly there isn’t a better education in sports, promotion, marketing,” she said. “I didn’t know where my career would go. I got the best education in the world with the Chicago White Sox, Bill, and Rudie Schaffer.”

Shoemaker grew up in Indiana. She was a radio-television-film major in the late 1960s and early 1970s at Purdue University. While still in college she got her first job on the production side at a West Lafayette television station. She came to Chicago in 1974 to work for the now-defunct Quadrant Productions, who held outbound feed production rights to the Chicago Stadium. A Quadrant production partner had a relative who worked for Oakland Athletics owner Charlie Finley (1944-2018) in his Chicago insurance office. Finley was looking for someone to coordinate administrative business for the A’s. Finley lived on a farm near La Porte, Ind.

St. Louis Browns era audition tape? (From the Veeck lost files.)

“That sounded interesting,” she said. “I didn’t know him. I knew of him because he’s an Indiana character as well.” Shoemaker got the job with Finley. “I wasn’t there very long until the paperwork about Bill Veeck buying the White Sox started coming across his desk,” she said. “I found it fascinating and found Bill interesting. Charlie was against Bill buying the ball club as were many others at the time. The sale went through (in December 1975). I knew the guys at WSNS-Channel 44, which did all the White Sox games.”

WSNS connected Shoemaker with White Sox television salesman Marshall Black. He got her an interview with Schaffer. In the middle of the interview, Schaeffer got up and immediately introduced Shoemaker to Veeck. In February 1976 she began work with the White Sox.

Judy Shoemaker’s life evolved into a gift, wrapped up in a box, bursting at the seams with passion, humor, and the best intentions towards fellow man. That, my friends, is Bill Veeck.

Dave:

Great piece on the history of Bill and the White Sox. We were delighted to see Judy Shoemaker when she was in town and hear the background on the files. Look forward to hearing more!

Thanks, Scott. Hope the film stuff is somewhat salvageable. See you soon!