Duke Slater: Passing the torch of a Chicago legend

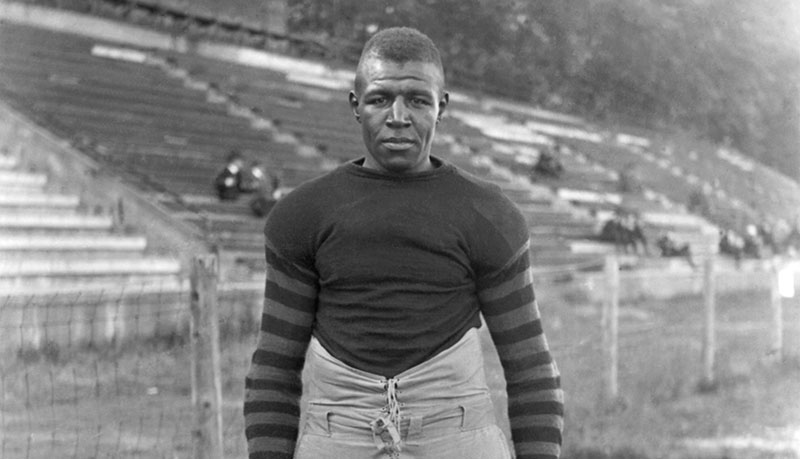

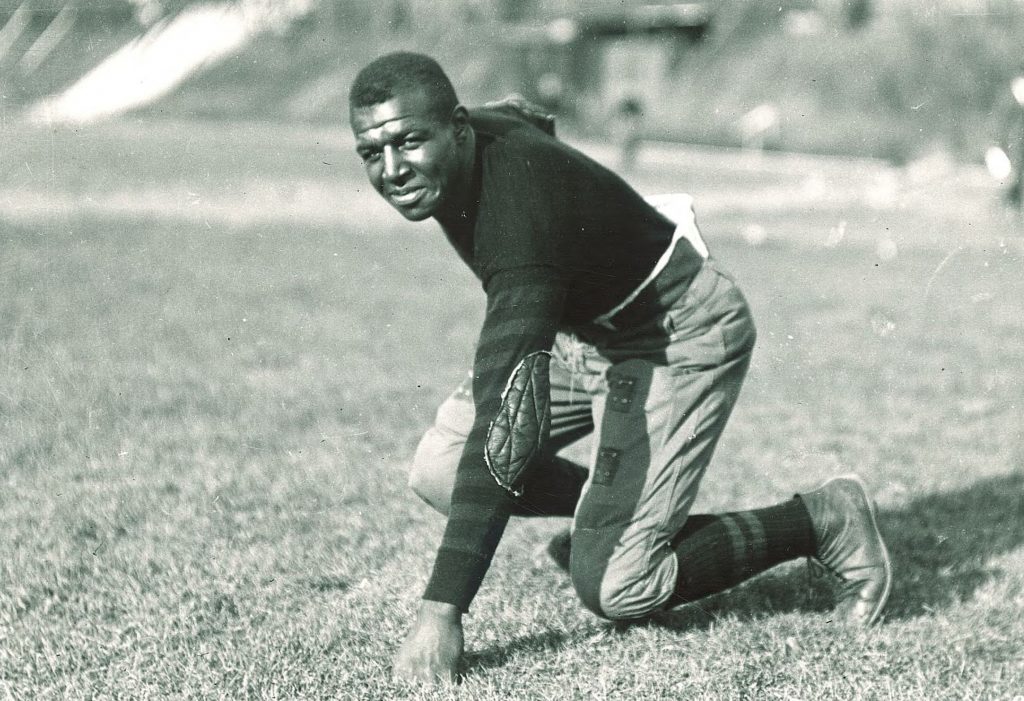

Duke Slater (1898-1966)

Once you learn that a good life comes from a series of small gains you will move on to bigger things. This is the ethos of football legend Duke Slater. Frederick “Duke” Slater was the first Black lineman in the National Football League. He played for the Chicago Cardinals between 1926 and 1931 and was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 2020.

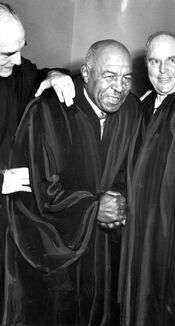

After his football career, Slater became an attorney on the South Side of Chicago and was the first Black judge to serve on the Cook County Superior Court. He earned his law degree from the University of Iowa in 1928 and practiced law while playing in the NFL. Slater died of stomach cancer in 1966 in Chicago. He was 67 years old.

Slater was born in Normal, IL. where his father was a Methodist minister. Young Frederick got his nickname from the family dog, “Duke.” When Slater was 13 the family moved to Clinton, Ia. where his father became pastor of the A.M.E. church in the Mississippi River town. Clinton was still a thriving lumber town. In the 1880s and 1890s, Clinton had more millionaires per capita than any other city in America.

Football Hall of Famer-announcer Terry Bradshaw spent his childhood years in Clinton after his father was transferred from Louisiana to work in production for area butane tanks. Slater, 6’1” and 215 pounds, played for state championship teams for Clinton High School and then went on to the University of Iowa where in his senior year the Hawkeyes claimed a share of the 1921 national championship.

Judge Slater in Chicago.

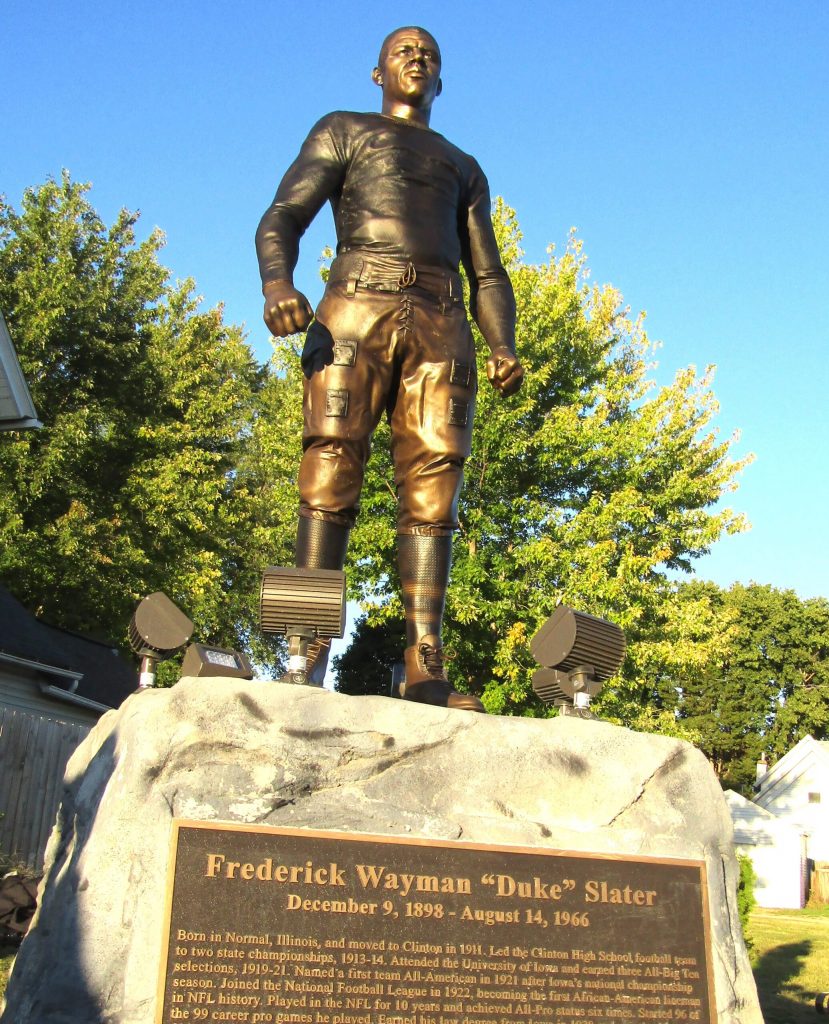

Slater still casts a long and proud shadow in Clinton (pop. 24,200).

Last fall a life-size bronze statue of Slater was dedicated in Duke Slater Pocket Park across the street from Clinton High School. Community leaders raised over $150,000 to create the statue made by Brodin Studios in Kimball, MN.

Ted Tornow is chair of the Duke Slater Statue and Scholarship Committee. He said the statue will not only “represent the students at Clinton High School, but to all people.”

Truth.

Tornow is a kindred spirit to all who look forward with empathy and hope. I got to know Tornow when he was general manager of the minor league Clinton LumberKings baseball team. The native of Menasha, WI. spent 25 years with the LumberKings. The LumberKing’s Riverview Stadium, built in 1937 by the WPA, still makes for one of the Midwest’s best baseball road trips.

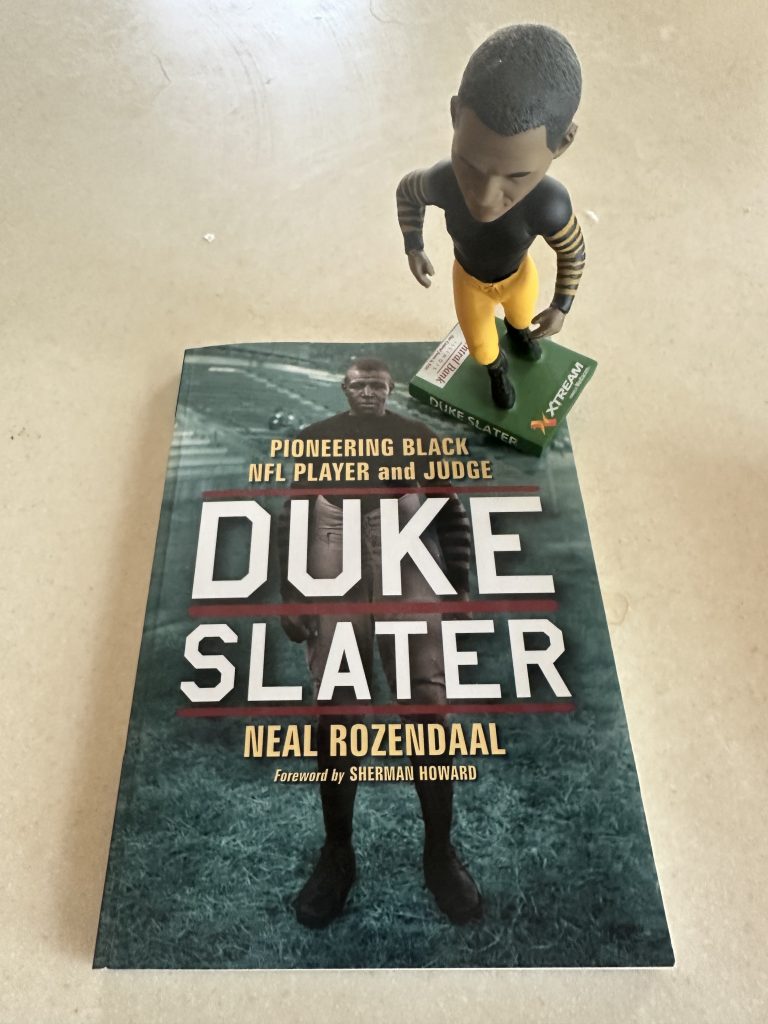

Tornow is a fan of the Mike Veeck “Fun is Good” spirit. He generally wore khaki shorts and Hawaiian shirts to work in Clinton. He once imported baseball pitcher-nightclub organist Denny McLain for an autograph session when few others would have him, and yes, in 2021 he had a Duke Slater bobblehead giveaway. Limited edition bobbleheads were also sold to raise funds for the scholarship and statue. Slater is in my office, next to Jerry Harkness of the pioneering 1963 Loyola Ramblers basketball team.

Tornow will never forget Clinton.

He is now Sponsoring/Marketing Manager at Surprise Stadium in Surprise, Az. but he remains a driving force in the first Duke Slater Memorial Scholarship. The gift provides $1,500 for the 2025-26 school year. It will be an annual award.

On April 25 the scholarship was awarded to Kaylee Moeller, a Clinton High School student who plans to major in psychology at the University of Iowa. ( In July 2021 the school’s football field was renamed Duke Slater Field at Kinnick Stadium.) Moeller turns 18 years old on May 15. Scholarship candidates had to provide academic information, attach letters of recommendation and fill out a four-question survey on the values of Duke Slater.

From left; Slater committee vice-chairman Gary Delacy, scholarship winner Kaylee Moeller and committee chairman Ted Tornow.

The final question on perseverance and “grit” caught my eye: “Duke’s life in the early 20th century was often filled with obstacles and limitations due to the color of his skin . Duke’s own perseverance and “grit” provided a road map to many of his successes on and off the field. What obstacles or limitations have you battled to overcome as you developed your own style of perseverance and “grit.”

Moeller answered in part through her experiences in sports. As a young athlete she embraced the volleyball team even though her skills had yet to develop and she took up tennis as a freshman even though she had never played the sport.

In 2012 Bureau of Labor Statistics economist Neal Rozendaall wrote the fine biography “Duke Slater (Pioneering Black NFL Player and Judge.)” In his introduction Rozendaal calls Slater “the most underrated athlete of the 20th Century.” In the chapter “Overcoming Adversity” Rozendaal reports how Slater spent college summer breaks hauling coal and gravel and laying bricks. Rozendaal wrote, “These off-season jobs allowed Slater to stay in shape and earn money for tuition, but they also created tales of his work ethic and strength that made him a campus legend.”

That’s grit.

Slater laid bricks by the Iowa Field House and the Burlington Street Bridge. He built a path; inch-by-inch, step-by-step. It is inspiring to know that a century after Slater’s work, University of Iowa basketball star Caitlin Clark walked portions of that same path.

Coincidentally, the Chicago Cardinals for which Slater played, had the first woman owner in NFL history. Violet Bidwill became the club’s owner after the sudden death of her husband. Now the Arizona Cardinals, the team is the oldest NFL franchise. The Cardinals took flight in 1901 as the Racine Street Cardinals (for their home field at Normal Park, 61st St., and Racine Ave.) before becoming the Chicago Cardinals in 1922. The Decatur Staleys left downstate Illinois in 1921 and became the Bears in 1922.

Rozendaal spent five years working on the Slater biography. “It would be great if Chicago came up with a recognition of Duke like their honorary street signs, ” Rozendaal said last week. “He had an incredible impact on Chicago. He was raised on the south side until he was ten. He learned to play football on the streets of Chicago. The Chicago Cardinals were the south side NFL team and he became a hometown hero.

“When the NFL banned Black players from the league in 1934–three years after Slater retired–he used his fame to organize and coach several Black all-star teams such as the Chicago Negro All-Stars, Chicago Comets, and Chicago Panthers. These teams gave talented Black players who were banned from the NFL, including great players like Ozzie Simmons and Kenny Washington ( a UCLA baseball teammate of Jackie Robinson) a platform to showcase their talents. That was a remarkable undertaking for which Duke doesn’t get enough credit. And then—he became just the second Black judge in the history of Chicago.”

The Arizona Cardinals have assisted with Slater fund raising efforts. “They were a major contributor,” Tornow said while keeping numbers confidential. “We’re still paying for things with the statue like bronze plaques for contributors and we have to tweak some lighting. The scholarship and statue money comes from the same place. We got some funding from the NFL Foundation. The Clinton Rotary Foundation. The Clinton County Development Association gave us $75,000.”

The new Duke Slater statue in Clinton, IA.

The project remains close to Tornow’s heart even though he is now 1,640 miles from Clinton. He flew back to Iowa for the scholarship presentation. “I want to see it through,” he said. “So many people don’t know who he is. At first, I thought it would be a great Mike Veeck shtick to have a (LumberKings) bobblehead before the Football Hall of Fame. Then it just morphed. Talking to Duke’s niece (in Fayetteville, Ga.) and seeing her give a speech years ago on how important Clinton High was to Duke. He came back and talked to the students and the football players. He did the same with the Iowa Hawkeyes. Or he would meet them if they were playing at Northwestern or Illinois.”

Rozendaal is a 45-year-old native of Grinnell, Ia.. He and his wife Ashley have three children: Magnolia, 10, Penny, 3, and a seven-year-old son Kinnick named after the 1939 University of Iowa Heisman Trophy winner Nile Kinnick. Rozendaal guided the committee through honoring the cornerstones of Slater’s life. He has lost track of Slater’s elderly niece.

From the Hoekstra archives.

Tornow called Rozendall the Slater family’s adopted brother. Tornow checked off the Duke-to-Do list. “Naming the (University of Iowa) football field, done” he said. “The Football Hall of Fame. Done. Recognition in Clinton. Done. There’s still no recognition of him in Chicago that I’m aware of.” Slater is buried at Mount Glenwood Memorial Gardens in Glenwood, Il..

Any readers like George McCaskey or Jerry Reinsdorf interested in helping honor Slater in Chicago should visit www.dukeslaterstatue.com. People interested in purchasing Rozendaal’s book should visit www.dukeslater.com.

The scholarship award was a surprise for Kaylee and her mother Jessica Patterson. “I was shocked,” Patterson said in a phone conversation over the weekend. “There has been a lot of talk about Duke Slater in our area after they unveiled the statue. With Duke being a football player I thought the winner would be a male (she chuckled.) Potentially a football player, but obviously….I’m proud of her. She’s always been open about trying new things.”

Moeller has played cello in the Clinton High School orchestra for four years, serving as section leader for two years. Her cumulative GPA is 4.24. She has been a member of the National Honor Society and volunteered at the Clinton Humane Society where she prepares animals for adoption by socializing them. Moeller wrote, “I was a camp counselor at summer camp and I have grown as a leader, as the oldest of my family and helping my mom with the foster children we brought into our home.”

Patterson obtained her MSW in 2013 from the University of Iowa and was a school social worker for the Clinton School District between 2013-22. She was a licensed foster parent from 2010 until 2019. More than 30 kids lived in her Clinton home during that period and Patterson adopted two of them.

“This scholarship is so meaningful because of Duke’s background,” she said. “Two of my children are Black and Kaylee is aware of the racism that continues to exist and has witnessed this towards her siblings. She understands that her race may offer more opportunity to have her voice advocate for issues directly impacting her siblings.” Kaylee’s 13-year-old and 8-year-old siblings were adopted and her 6-year-old sibling is biological from Patterson and her husband Chris. Moeller is her biological daughter from her previous marriage.

Patterson has also been a relationship and wellness strategist for adoptive parents. She said her daughter’s family dynamics “definitely” informed her decision to pursue psychology.

Tornow will be behind the Slater project for the long run. “It’s important to me,” he said. “At some point, Kaylee will remember she was the first scholarship winner. She’s getting into psychology, who knows if this will impel her to bigger and greater things? Benefit mankind? You don’t know. We have to start somewhere.”

Inch by inch, yard by yard.

Leave a Response