Discovering a City Abandoned

|

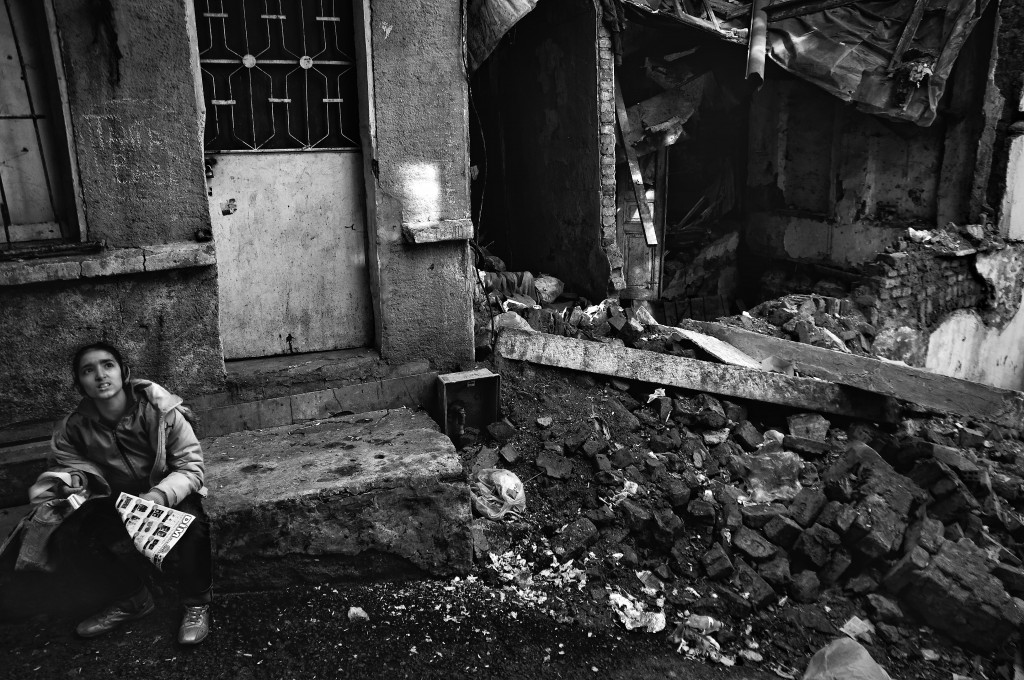

Istanbul is an old city of deep shadows. The density of 14 million people, regal mosques and the history of the capital of Turkey creates a humble stage. Istanbul has been the capital of four empires, ranging from the Roman Empire (330-395) to the Ottoman Empire (1453-1922). We are all just passing through. In March, 2012 I visited Istanbul. Chicago photographer Hector Maldonado and his wife Selin-Isin-Maldonado were my weekend tour guides and they took me to places I will never forget: coffee shops in Cihangir, which overlooked Bosphorus (the strait that connects the Black Sea and the Sea of Marmara), a small bar in a dark alley where the walls were filled with hardcover books from floor to ceiling and a stroll down Istiklal Street where our voices were muffled by the steady hum of Saturday nightlife people. Hector carried two cameras everywhere we went. He found light in the veil of the mysterious city. And now 24 of his Istanbul portraits hang in his “City Abandoned” exhibit on the second floor Rangefinder Gallery at Tamarkin Camera, 300 W. Superior St. in Chicago. His show is up through Nov. 29. Hector is a kind man with open eyes. Before my 2012 trip he was referred to me by our mutual friend Tony Fitzpatrick. Hector and Selin dropped everything to show me around their adopted city. The story Hector shares with Selin makes me happy. Hector was born in 1962 in Bridgeport from a Native American mother and Mexican father. He was trained as a chemical reactor operator. Selin was born in 1975 in Istanbul and grew up near the seaside Asian side of the city. She was running an art gallery in Istanbul in 2002 when Hector visited with his artist brother Jeff Abbey Maldonado. (In 2009 Jeff’s son was gunned down in Pilsen on the day of his 19th birthday and became the subject of the acclaimed “19 and a Day” documentary.) Hector met Selin at the Istanbul gallery. They married 10 months later. They are good to each other. In September, 2009 Istanbul became a permanent home for Hector and Selin. Her mother Nurseli died of a brain aneurysm in 2001 and Selin wanted to take care of her father Ali. Hector and Selin returned in May of this year to settle back in Chicago. In April, 2013 Hector and Salin were visiting Chicago to celebrate their 10th wedding anniversary. They were eating sushi at a north side restaurant when Salin stepped outside for a celebratory cigar. It was her first cigar in two years. She collapsed and began vomiting. She also suffered a brain aneurysm. While she was at Northwestern Memorial Hospital she called her father in Istanbul to say goodbye. “It was serious,” she said last week in a conversation at the Tamarkin gallery. “They gave me a 20 per cent survival rate. I’ve lost some of my memory. I’m re-learning words in Turkish and in English. All the women in our family have brain aneurysms. It is a genetic disorder. I’m the only one who has survived it. My grandmother, my mother and aunt died from it. Because of mine they tested my cousin and they found hers without it rupturing. “I have two more unruptured ones on the right side of my brain. They are keeping a close eye on them. In a way, it is like a time bomb.” Hector looked at his wife. They were sitting side by side on a black couch in the gallery. They have moved forward together in a new light. Selin continued, “I had a second chance at life. I didn’t want to waste it there. I could be part of a protest by chance and get hit or shot and killed. I did not feel safe in my country. The political unrest was very hard for me to see. We would be having lunch and all of a sudden people are running through tear gas. Or getting beaten. I did not feel safe in my country.” Hector’s portraits honor the Tarlabasi neighborhood of Istanbul. The area was settled in 1535 by non-Muslim diplomats and became the neighborhood of the non-Muslim lower middle class. Selin reflected, “The buildings were beautiful, made of iron work and with beautiful murals. After the war, the people were forced to leave leaving their stuff behind. Once the government realized these were million dollar lots, they said, ‘Let’s build a new city there.’ And they started forcing these families out. The last time we were there (2013) they cut their water and electricity so people were literally taking wood from the floors of the building to heat their apartments. Now it is gone. I wish they had restored a couple of these buildings. Now they are building cement, cookie cutter things.” Hector made his pictures of gypsy kids and gentle grandfathers between 2005 and 2013. He shot on film on his 1957 Leica and developed the photos himself. “I usually don’t like posing but I used some of that,” he explained. “Sometimes I wait to see what happened. You have to be close. It took me awhile to start taking pictures of people. Istanbul has fantastic faces of people. I started taking pictures real quick without them noticing. I try to wait for moments. I respond to stuff. The Leica (camera) is very quiet. Primarily I shoot in black and white because it adds to the timeless feature” In a Wednesday e-mail Gallery owner Dan Tamarkin wrote, “Hector Maldonado’s Istanbul work is punctuated by urban detritus countered by portraits lovingly rendered, as if to mimic the high contrast of the lighting in his images. Shot from the hip and usually with minimal preparation, Maldonado’s photographs are stirring records of the moment, a time and a place. And in many cases, these people and places no longer exist, which makes his work all the more important from a documentary perspective; a mirror held up to our own lives and and to the lives of people in far-flung places, a visage many of us never get to see. His work is timely and timeless–a series of light and shadows that allow us to see beyond the glare of the media and into the lives of the people and places of Istanbul–and wherever his travels take him.” Hector had empathy for his neighborhood subjects. “Growing up, I fought a lot,” he said. “I was a skinny kid. A quiet kid. But I took judo. I wrestled. We weren’t rich. We lived in a flat.” His mother Ina Abbey was a social worker at a Cabrini-Green clinic. His retired father Jesse worked in robotics maintenance at General Motors. Selin’s mother was a professor of radiology in Istanbul and her father worked in international economics. “I got more serious about the Istanbul neighborhood over the last three years,” he said. “The neighborhood ended up being like Cabrini-Green in Chicago. Everyone was kicked out by developers. Corrugation was put up at every block to keep the people out. “The neighborhoods aren’t as big as they are in Chicago. This neighborhood was very poor and grittier so I like that. I ended up going places where I knew shadows would be good because there’s drama. When I started going to this neighborhood everybody told me not to go there. Everybody. But I liked the place. How were they going to stop me? I’m a grown man.” Hector spent so much time in the neighborhood he began to earn the trust of the residents. Kids would run up to greet the bear of a man with tattoos on his arms. The large tattoo on his right arm was designed by one of Selin’s friends. The ink reflects the spirit of his Alabama-Coushatta tribe. The original cress is called “The Twin Manifestations.” He said, “The Great Spirit had bestowed upon man the priceless gift of free will of which each individual makes his own choice between ‘good’ and ‘evil.,’ this is a fundamental teaching of the Alabama-Coushatta Tribe.” This is why Hector’s imagery reminds me of the great Istanbul photographer Ara Guler. Guler was influenced by the portraits Edward Curtis (1868-1952) took of American Indian chiefs and has said his work reflected a natural feeling for composition. In his artist statement Hector said, “Being with a camera is the best way I have found to feel close to the earth again.” He elaborated, “Our tribe comes from a hole, a cave. The earth created us. Alabama-Coushatta—that’s the white man’s way of saying it—is the oldest reservation in Texas. My uncle is chief of the tribe. I try to stay involved. We just went to the Pow Wow in Chicago. Some Indians came to my opening so I was very happy about that. “It is who I am, it is part of me.” It helps him see the light.

|

Leave a Response