The Eternal Soul of Otis Clay

|

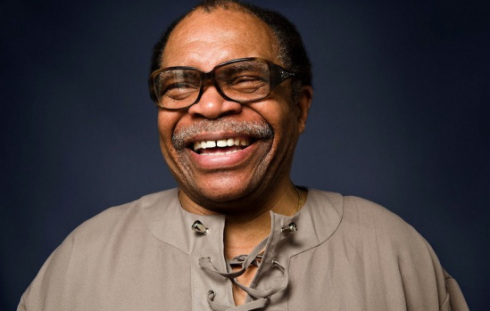

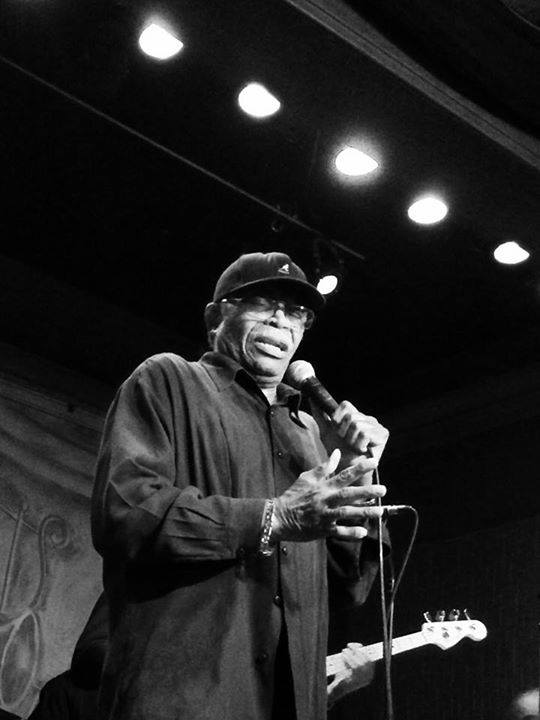

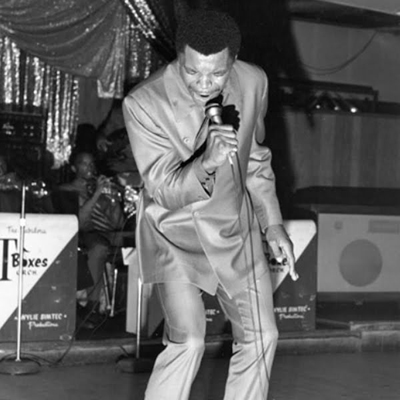

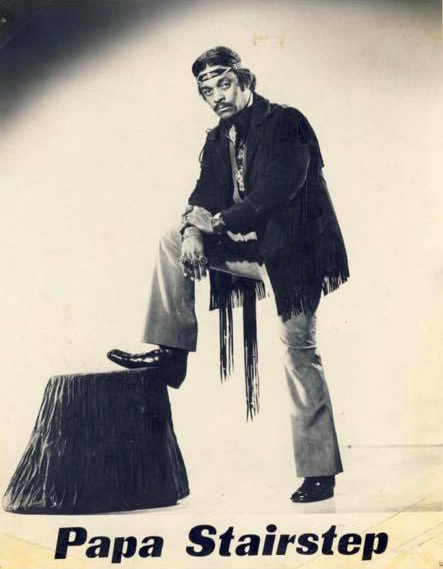

Over the past 50 years Mr. Clay became the city’s greatest soul singer, one of the last of America’s pure soul singers and a cultural ambassador. Mr. Clay died of a heart attack Friday night. He was 73 years old. What is soul? Soul is eternal love, soul is brotherhood, soul is empathy. Take notes. Mr. Clay must be on a mission to get things straight in the city he called home since 1956. Of course Bob Seger had a smash hit with Mr. Clay’s 1972 regional hit “Trying to Live My Life Without You” and Mr. Clay was always a riveting performer at his Liberty Baptist Church, 49th and King Drive. In the summer of 2005 Robert Plant took time out from his tour to catch Mr. Clay’s set at the Old Town School of Folk Music’s Folk & Roots Festival. He knew Mr. Clay was essential soul. But most important of all there was Mr. Clay’s smile that stretched like a ribbon of understanding. No dark days here. Mr. Clay was a decent man whose warmth touched all those he met. He was always ready to assist a needy musician, organizing benefits and concerts for his compatriots like the late Tyrone Davis and former Koko Taylor guitarist Vino Louden. When it wasn’t so popular, he was chairman of the non-profit Tobacco Road, Inc., which managed the ill-fated Harold Washington Cultural Center in Bronzeville. He was a passionate advocate of Bronzeville arts. I would see Mr. Clay in the audience of countless funerals for Chicago gospel greats. He represented. I knew Mr. Clay for 33 years. He was always willing to help me out. On Oct. 29 Mr. Clay and his band headlined our book release party for “The People’s Place (Soul Food Restaurants and Reminiscenses From the Civil Rights Era to Today)” at FitzGerald’s in Berwyn. He did not ask for a cover charge and many guests attributed the feeling of fellowship that night to Mr. Clay’s songs and civil-rights era stories. He knocked out the house with covers of Joe South’s “Walk a Mile in My Shoes” and the extended version of Sam Cooke’s “A Change is Gonna Come.” The show, which attracted a large black and white audience, turned out to be Mr. Clay’s final Chicago area appearance. Earlier in 2015, Mr. Clay and keyboardist Max Brumbach brought in a nine-piece band to play on my WGN-AM Saturday night radio show. Mr. Clay still holds the house record for cramming musicians into the station studio. Mr. Clay was a willing participant to sing in the annual Buck Owens birthday tributes produced by my friends John Rice and John Soss and Mr. Clay was one of the first in line, along with Paul Cebar and Mavis Staples birthday tributes produced by my friends John Rice and John Soss, and Mr. Clay was was one of the first in line, along with Paul Cebar and Mavis Staples to appear at my 2000 “Ticket To Everywhere” book party at FitzGerald’s. At that event he delivered a saucy version of Don Covay’s “I Was Checking Out, She Was Checking In,” and true story: My Mom name-checked Mr. Clay’s performance almost until the day she died. Mr. Clay was born on Feb 11, 1942, the youngest of 10 children raised in Waxhaw, Miss. His father was a farmer whose nickname was “Sing” Clay, although Mr. Clay admitted pops wasn’t such a hot singer. At night Mr. Clay liked to listen to the Grand Ole Opry out of Nashville. During the day the Clay children sang in a family gospel that patterned themselves after the Dixie Hummingbirds. In 1956 Mr. Clay left Mississippi to live with his aunt and uncle at 119 E. 45th St. in Chicago. Mr. Clay first went on the road as professional singer in 1960 with the Famous Blue Jay Singers, who recorded for Trumpet Records out of Jackson, Miss. Mr. Clay had been drafted from the Golden Jubalaires, a group of young Chicago-based gospel singers. In 1964 Mr. Clay began singing with the Sensational Nightingales and remained with them until the middle of 1965, when he crossed over into soul. Stepping out as a lead singer in a gospel group, Mr. Clay embraced harmony. By the 1960s gospel harmonies became more robust, accenting the role of lead singer. Strong voices emerged such as falsetto Claude Jeter of the Swan Silvertones and Sam Cooke of the Soul Stirrers. “My first professional gig was 1960 in Ludlowville, New York,” Clay told me in a 2010 interview commemorating his 50 years in the music business. “The Blue Jays were singing a capella and that’s where harmony really paid off. Everybody can’t do harmony, We used barbershop quartet chords. Everyone was thinking about the weirdest chord to get people standing on their feet.” Because of Chicago’s profound blues imprint, Mr. Clay’s soul and rhythm and blues could be taken for granted in his hometown. During the mid-1990s a regular group of us got together on the last Thursday of every month to see Mr. Clay’s residency at the tiny B.L.U.E.S. on Halsted. At the same time, he was playing 50,000 seat arenas in Japan. Mr. Clay championed other Chicago soul singers like Cicero Blake and the late Lou Pride. In May, 1996 when the mysterious Memphis soul singer James Carr made his final mesmerizing appearance in Chicago at Rosa’s, he used Mr. Clay’s backing band. Mr. Clay was in the audience, cheering Carr on. One of the last times Led Zeppelin played Chicago Stadium, soul singer Bobby Bland was headlining the Burning Spear nightclub at 55th and State. Mr. Clay was a few miles away at a small West Side social club. After the 1973 Zeppelin gig, Robert Plant led a fleet of six black licorice limousines to the Spear to catch Bland’s late set. Mr. Clay drove his midnight blue Mark IV to the Spear. Mr. Clay and Bland jammed together, accented by the Burning Spear chorus line. Plant was star struck about meeting Mr. Clay. He emulated Mr. Clay’s gospel vamp in numerous covers of Mr. Clay’s 1966 hit “It’s Easier Said Than Done.” After telling me that story in 1988, Mr. Clay stopped and smiled. “What is it that makes a man rich?,” he asked. “You’ve contributed something. Somebody liked something you’ve done.” Mr. Clay sang the slow blues number “This Time I’m Gone For Good” at Bobby Bland’s 2013 funeral. After scoring a 1968 rhythm and blues hit with a straight no-chaser cover of Doug Sahm’s “She’s About a Mover” on Cotillion/Atlantic Records, in 1970 Mr. Clay met the late Hi Records producer Willie Mitchell (Al Green, Syl Johnson and O.V. Wright) . Cotillion had dispatched Mr. Clay to Memphis to record “Is It Over”. By 1971 Mr. Clay signed with Hi snd Mr. Mitchell produced most of Mr. Clay’s biggest hits, “Precious, Precious,” “Holding on to a Dying Love” and “Trying To Live My Life Without You.” In the summer of 1983, Mr. Clay was involved in a near-fatal automobile accident. He suffered nine broken ribs and spent 15 days in the hospital. People told him he would not be able to sing again. “But my whole style changed after the accident,” he told me in 1991. “I was able to do peaks. My earlier records sounded strained.” Not long after the accident, he was reunited with Mitchell and they recorded 1988 tracks at Mitchell’s Waylo studio in Memphis. In an interview later that year, Mitchell said, “Otis is singing better than he did 10 years ago. He’s mellowed with the times. See, Otis sings songs. Gospel songs, country songs, rock n’ roll. I just set up the mike and let him go.” In 1991 Mr. Clay went to Memphis to record the underrated “I’ll Treat You Right” album for Bullseye Blues Records that featured the Hi Rhythm Section and the Memphis Horns (Andrew Love, Wayne Jackson). The album is a stunning mix of secular and gospel music, including Johnnie Taylor’s “Love Bones” and a searing version of the Salem Travelers “Children Gone Astray.” Mr. Clay’s deep soul was not lost on Chicago blues guitarist Dave Specter, who featured Mr. Clay on three tracks from his 2014 “Message in Blue” project for Delmark Records, including “This Time I’m Gone For Good.” They also locked in with a spine-tingling cover of the 1965 Wilson Pickett hit “I Found a Love.” “Otis had such a giving spirit,” Specter said on Saturday. “He was such a sweet, humble guy. Patient. (Specter’s voice broke.) He had this deep intensity on stage that gave you goose bumps and made you cry. Then, when you talked to him, it was like talking to a family member. I was going through a bad breakup of a relationship when I was recording with him. I leaned on him for help sometimes. And he was there for me.” So, what is it that makes a man rich? The answer is not found in ambition and glory. It is not found under the lure of a spotlight. It is about knowing who you are, a life tethered into meaning. Mr. Clay lived that life well. He was a true soul and a true friend. And soul is a guiding star that never dies. |

Dave,

As the Director of Development for the Chicago Coalition for the Homeless, Otis Clay donated a performance to Hope fest for the 10 years I was the Director. Otis did so willingly and with a Spirit of generosity to raise money for those less fortunate. Not only was he a great soul singer; he was a humanitarian and should be remembered equally for his unselfish gestures of kindness. Ellyn