The Day I Visited Mad Magazine

NEW YORK- A set of snare drums are poised behind the editor’s desk, goofball toys landscape his office like tripped war mines and you need a flyswatter to squelch all the punch lines.

It’s the frat house on Madison Avenue.

The 13th floor at 485 Madison is anchored by the worry-free digs of Mad magazine, the purveyor of fast-food satire that is in the midst of feasting on its 35th anniversary. Maybe Jimmy Buffett’s “Growing Old But Not Up” is the appropriate soundtrack for such sophomoric sentimentality. In fact, editors John Ficarra, 32, and Nick Meglin, 49, with their seasoned beards and receding hairlines, look like a couple of professional college students.

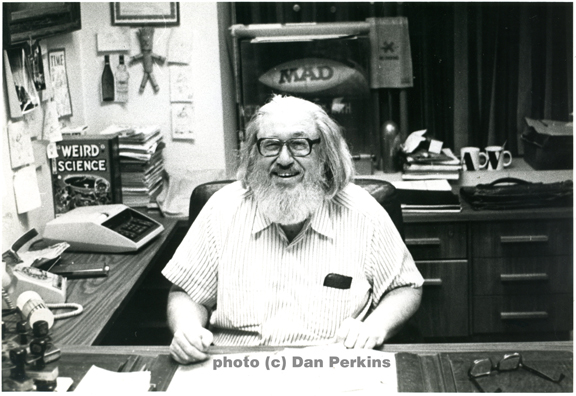

The nutty professor remains Bill Gaines, the 65-year-old founder of Mad.

A ringer for a reclusive-era Howard Hughes, Gaines entered Ficarra’s office in a mystical manner on this fall afternoon, his silver beard and shoulder-length white hair heralding the presence of a guru. Gaines wore greasy black slacks that could walk on their own and a plain white shirt, documenting the purity that those who know him respect so much.

“Aw, I’m just trying to be friendly,’ Gaines shrugged, sprawled out on a sofa in Ficarra’s funky office and speaking in deep down-home, uptown tones. “We have kind of a family feeling about this place. Every year we take our staff on a (all-expenses paid) weeklong trip and this year we went to Paris. We took along a new member and she was absolutely amazed at the togetherness of this outfit. We really do things like hug each other when we meet.

“It’s something we’ve taken for granted a long time.”

Meglin is beginning his 32nd year at the magazine. Working at the madhouse was the first job he had out of art school. “Bill told us that none of us would get raises if we wore a tie,” Meglin said, wearing a loose-fitting polo shirt and sitting across the room from Gaines. “If I had to wear a tie and a herringbone suit every day, it would be horrendous. That’s the kind of atmosphere there is around here. The fact that we’re the biggest slobs on Madison Avenue is OK with us.”

And these big slobs are doing OK.

With U.S. circulation close to 1 million and another 400,000 delivered through 11 foreign editions, last year Mad grossed nearly $9 million. Gaines has just seven full-time employees and a larger stable of free lancers. He doesn’t employ a secretary and he doesn’t permit expense accounts.

Gaines ‘ roots were peppered with such frugality. His father was a New York publisher who produced innocent and simple picture stories about bunny rabbits, cowboys and the Bible. Gaines was studying to be a chemist when his father suddenly died, leaving his son the business.

As sons are known to do, Gaines put his own twist to the business.

“I started putting out comics like `Tales From the Crypt,’ `Vaults of Horror’ and `House of Fear,’ along with a couple of war books,” Gaines said, grinning. From behind his desk, Ficarra interrupted, “You were married then, Bill?”

Gaines fielded the barb as smoothly as Luis Aparicio and continued, “The reason that Mad was born is absurd, but it is the truth. I had two editors in those days. One was putting out seven titles and the other was putting out two. I paid by the title and by the issue.

“The guy (Harvey Kurtzman, who’s better known for his “Little Annie Fanny” in Playboy magazine) who was putting out the two was slow and he was disgruntled because the other guy was making 3 1/2 times as much. But he was funny and he had come to the office with all this funny material. So I said, `Harvey, why don’t you put out a humor book? You can do it quickly, you don’t have to research it, just throw it in with the others. And that was the honest-to-God reason there’s a Mad magazine. Just to up his income.”

The wholesome Mad humor didn’t emerge until the fourth issue of 1952 when the magazine began to attack other comic-book characters. Meglin said, “That’s when it took on a dimension of satire. Before that, it was humor for humor’s sake and it was silly.”

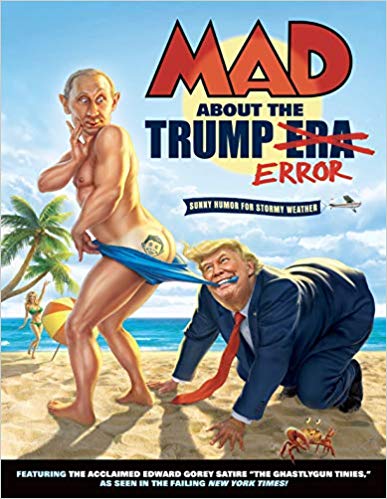

The two editors and Gaines, who is now the publisher, agreed the magazine has changed very little in 35 years. Meglin said, “The magazine doesn’t change in that we reflect the society that we live in. The society keeps changing so naturally our mirror image of it (through satire) changes. But we don’t really change because we don’t create anything. We just respond to what’s out there. We can’t make up the kind of garbage that goes on in politics. They’re much better at it than we are.”

Ficarra said, “If we were to come up with the Jim and Tammy thing, no one would believe it. How are we going to top that?”

(Donald Trump did.)

If Mad waned during its 35-year run, it was in the early ’70s, with the crest of National Lampoon’s punch-the-envelope humor, which in turn influenced “Saturday Night Live.” Lampoon pushed the boundaries of bad taste, featuring lots of breasts, earthy humor and the famous cover that threatened: if you didn’t buy the magazine, your dog would be shot. As Rolling Stone was to Teen Beat, National Lampoon was to Mad.

Mad has tumbled from a circulation of 2.4 million in the mid-’70s.

“We used to have a readership from 10 on up to college and for a time Lampoon took our college readers,” Gaines admitted. “I think they’ve lost most of them back (to us). Generally, our readers do leave us for Lampoon or Playboy, but after college they come back to us.

“That’s not a hard and fast survey, because we don’t do hard and fast surveys. That’s just judging from the mail we get. But 10-year-olds are much more sophisticated today because of television, and things like `Saturday Night Live’ educate them in outrageous humor. I think they pick up more than we did 20 years ago at the same age.”

Gaines’ fiscal conservatism has allowed Mad to absorb the circulation drop with the approval of Warner Communications, to whom Gaines sold the magazine in 1967. Warner gives Gaines a free rein over Mad, accepting quirks such as the magazine being printed on low-rent stock, no promotion or sales staff and a steadfast refusal to sell his subscription list.

The clear advantage television humor has over Mad or even National Lampoon are immediate deadlines. “Saturday Night Live” is a weekly show that is focused around current events. “We just can’t do that,” Ficarra said. “We really have to pick our targets. Like now (in mid-November) we’re working on our February and March issues. We have to take a longer view of everything.” That’s why through the years Mad has poked fun at movies, television shows and advertising campaigns. “Those are the things that last,” said Gaines.

The Mad honchos are proud they’ve steered away from the toilet for 35 years. The editors agree Mad doesn’t do “gratuitous obscenity.” Gaines confessed, “Oh, we get gross once in a while, but not in a gross way.”

Ficarra said, “We have a special (magazine) coming out called `Mad Gross Outs’ in which we’re going to feature 50 pages of our grossest material. We had a hard time pulling it together. We put in `The Exorcist,’ which had Linda Blair puking her guts out. But, again, we were just mirroring the movie.”

Gaines has the deal curtain-closer planned for Mad.

“We’ve always had the idea that all the gross stuff would be saved for our last issue,” he said.

Gaines is proud of his writers and his fierce respect allows them the latitude to write for themselves, which has always been the attitude at Mad. Gaines pays free-lancers (between $300 and $550 per magazine page) the minute they drop off their copy.

“Our writers are of primary importance,” he said. “I’ve always had the theory that without writers there would be no theater, no movies, no television, no books, no roller derby. You gotta start with a good, strong, punchy script. After that we have what is the best staff of artists in the world.

“This is a writer-oriented magazine. We rarely assign a topic to write, except for movies and television shows. Almost all other ideas come from the writers. Editors will help them develop the ideas. The more (ideas) they sell, the happier we are.”

Meglin did have an admission to make.

“Sometimes we write (ideas) down, only so our publisher will understand what we’re doing,” he said. Ficarra spun around in his chair and banged the cymbal on his drum.

Are we having fun yet?

The funniest thing about some of the Mad ideas is that they moved from jokes to serious proposals. Probably the most famous is Mad’s 1966 suggestion to put advertising on postage stamps. In 1981, Rep. Barry Goldwater Jr. (R-Calif.) proposed the Free Enterprise Postage Stamp Act allowing domestic corporations to promote their logos on stamps to raise money for the perennially strapped Postal Service.

“Before that, one of our writers came up with the idea that a population explosion becomes a garbage explosion obviously because there’s more waste,” Meglin said. “So the way to handle it is to project garbage missiles into outer space. So one reader, word-for-word, rewrites it and sends it to his congressman. The congressman in turn, reads it into the Congressional Record as a viable thought.”

Ficarra said, “One of our writers, Al Jaffe (best-known for “Snappy Answers to Stupid Questions”), is extremely creative and has had numerous ideas in the magazine that people have patented.”

Meglin continued, “Al projected the parking problem was so bad in some cities that new parking plans had to be developed. One idea was a parking Ferris wheel, because you have more air space than ground space. Sure enough, about six months later, designs were being made for this in some other country.

“Or as a gag, we wrote that George Steinbrenner would hire and fire Billy Martin four times. It was a highly exaggerated takeoff. It came out three years ago and when we did it everyone laughed. No one thought it could happen.”

Ficarra wondered aloud if the magazine could ever get funnier than Steinbrenner. “Can we really do it?” he said. “I don’t think so.”

For all his delightful iconoclasm Gaines has guarded Mad well. For the past 35 years, he has vetoed commercial endorsements, merchandising and movies. “I just felt it wasn’t proper to suck every buck out of everyone,” Gaines said. “I’ve recently had a change of heart and we are now going to carefully do what we call creative merchandising.”

So in January, you can expect a Mad wristwatch that features the baffled Alfred E. Neuman in a straitjacket with his feet moving around the clock. Gaines’ one concession to merchandising, a Parker Brothers Mad game (where winning requires losing all your money) is being reissued next year.

“Bill and I strongly disagree on this point, but I feel that many of our readers associate with the magazines so much that they look for certain gimmicks or merchandise,” Meglin said. “It’s like when I go on a trip somewhere, I don’t know why, but I buy an ashtray. I don’t smoke. But you want an association. But Bill doesn’t see that because he is such a purist and an idealist.”

And that reflects Mad’s notorious no-advertising policy, which has its roots in Chicago. “It began with a newspaper, PM (whose staff included Dorothy Parker), and it’s a shame that nobody knows about it anymore,” Gaines said.

“Marshall Field of Chicago took a lot of money and gave it to Ralph Ingersoll to start a New York paper that would not take ads. The basis of the paper was that you can’t take an ad from somebody and not be beholden to them. In those days there was no such thing such as running an anti-cigarette story because they were terrified of losing their cigarette advertising.

“So PM comes along and tears into everything, takes no ads and doesn’t give a shit. And for six or seven years they had a wild time. Unfortunately, PM cost a nickel and the Daily News cost 2 cents. After World War II it died unhappily. But I was brought up on PM. . . . Those were my formative years and I was always taken by the concept.”

—

Leave a Response