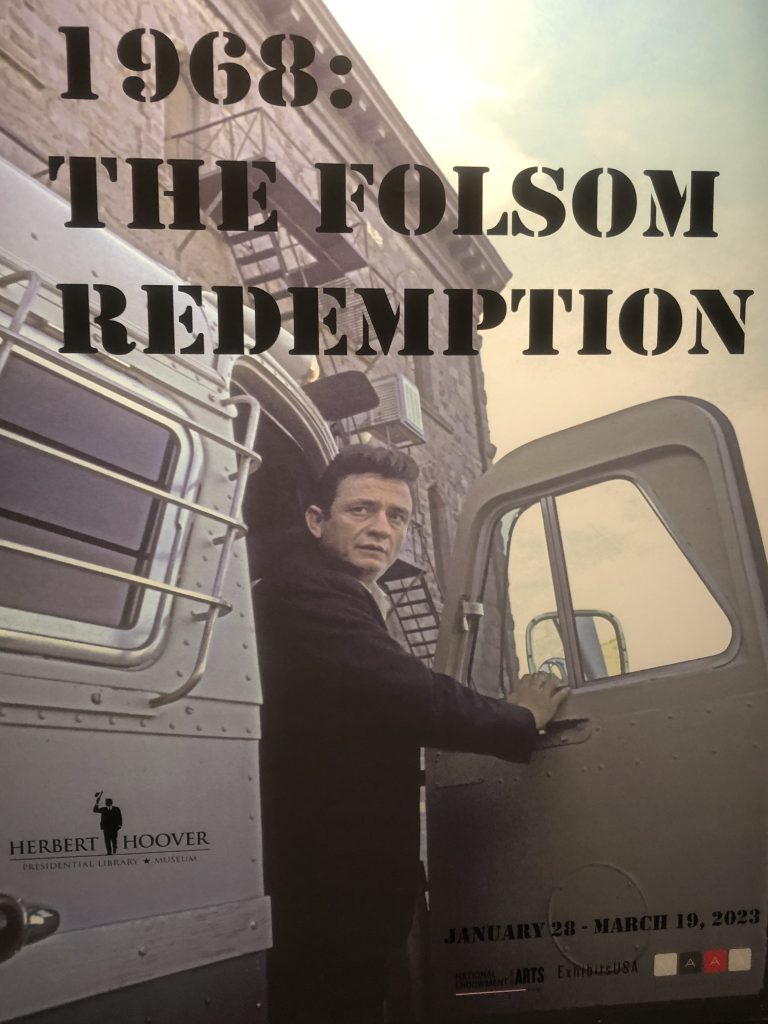

Johnny Cash meets Herbert Hoover on the Road to Redemption

Johnny Cash at Folsom Prison, Jan. 13, 1968 (Dan Poush photograph.)

WEST BRANCH, Ia.—This road of incongruity was too much to pass up.

I’ve driven past the sign on I-80 for the Herbert Hoover Presidential Library and Museum at least a dozen times on my way to Iowa City, the Iowa State Fair, or a minor league baseball game. I never stopped to see the museum. After all, in a 2021 CSPAN survey, presidential historians ranked the 44 presidents. Hoover came in 36th due to his legacy of economic woes. Months after his 1929 election the stock market crashed and the United States fell into the Great Depression.

But when I was in Iowa City last week to see songster Greg Brown’s retirement show, I heard about the current exhibition at the Hoover Presidential Library.

“1968: A Folsom Redemption” is a collection of 31 photographs and interviews from freelance photographer Dan Poush and freelance writer Gene Beley who chronicled the historic Johnny Cash concerts before 300 inmates at Folsom Prison near Sacramento, Ca.

The exhibit features breathtaking images of Cash, June Carter Cash, and Merle Haggard meeting Cash backstage in the granite jungle. Haggard had done time in San Quentin. Carl Perkins and the Statler Brothers were Cash’s opening acts at Folsom Prison. Another room has a screening of the 2008 documentary “Johnny Cash at Folsom Prison.”

Cash getting off prison bus before his first show, which was 9:40 a.m. Note the Hoover logo on left.

So at one moment in time on a President’s Day weekend, I was watching Cash and his band the Tennessee Three on a prison stage belting out the Western swing traditional “Cocaine Blues” at the Hoover Presidential Library.

The traveling exhibit was organized by Exhibits USA, a program of the Mid-America Arts Alliance. It is at the Hoover Library through March 19. West Branch is about 20 miles east of Iowa City.

The Cash exhibit was in West Branch (pop. 2,500) because Hoover was a champion of prison reform. His work led to the passage of eight bills that alleviated prison overcrowding, the building of new penitentiaries, and the establishment of a federal school for prison guards.

According to World Biography U.S. Presidents, the number of prisoners on parole multiplied during the Hoover administration. Hoover was a Quaker and prison reform and Indian policy were areas of interest to Quakers. (Richard Nixon is the only other Quaker who became president.) Illinois social reformer Jane Addams voted for Hoover in 1928 and 1932.

I did not know some of this until I visited the museum.

The museum is a National Historic Site and offers more than I imagined. Visitors can walk into the Friends Meetinghouse (circa 1857) where Quakers held their services. Hoover’s mother Hulda was a minister and his family worshipped in the house adorned with wooden benches. The building has been moved two blocks from its original site. Hoover’s gravesite is on the grounds and in keeping with modest Quaker ethics there is no mention of him being president on his headstone.

After Hoover lost the 1932 presidential election to Franklin Delano Roosevelt, he went into a 32-year retirement that included a residency in a four-room suite at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel in New York City. When Hoover grew weary of hotel food, he sent out for baked beans at the nearest Horn and Hardart Automat. His neighbors included Cole porter and the Duke and Duchess of Windsor. Hoover died in his Waldorf Astoria suite in 1964 at the age of 90. The museum includes a 1940-era recreation of his Waldorf Astoria office space.

Trump Tower had yet to be built.

Hoover’s wife Lou Henry Hoover attended Stanford University where she was the first female geology major in the United States. The Waterloo, Ia. native was an ardent supporter of women’s rights–encouraging women to establish careers away from the house– and was head of the Girl Scouts between 1922-25 and 1935-37. In part, she blamed the news media for her husband’s failed re-election. She suffered a fatal heart attack in 1944 in New York City.

By 1945 President Harry Truman invited Hoover back to the White House and the two men established a friendship that lasted until Hoover died in 1964. Truman was a Democrat. Hoover was a Republican. They worked together.

It was fascinating to see this history through today’s fragmented lens.

It was also interesting to connect the dots.

John Cash at the Hoover Presidential Museum 2/17/23

There’s Haggard, whose family migrated from Oklahoma to California in the 1930s grit of the Dust Bowl when Hoover was still reeling from the stock market crash. Before becoming president Hoover was regarded as a humanitarian. As the U.S. Secretary of Commerce, he played a key role in organizing relief during the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927.

Haggard was born on April 6, 1937, in Bakersfield, Ca. Haggard was serving time in San Quentin for robbing a roadhouse when Cash performed at the prison in January 1959. It was the first time Haggard saw Cash in concert. He was released on parole in 1960. So Haggard’s renegade life was in part, shaped by Hoover’s misfortune.

The museum does a good job of presenting a balanced account of Hoover’s tumultuous tenure. One panel features a Will Rogers letter to the New York Times after he lost to FDR. In part, Rogers writes, “It wasn’t just you Mr. President. The people just wanted to buy something new, and they didn’t have any money to buy it with. But they could go out and vote free and get something new for nothing. So cheer up. You don’t know how lucky you are.”

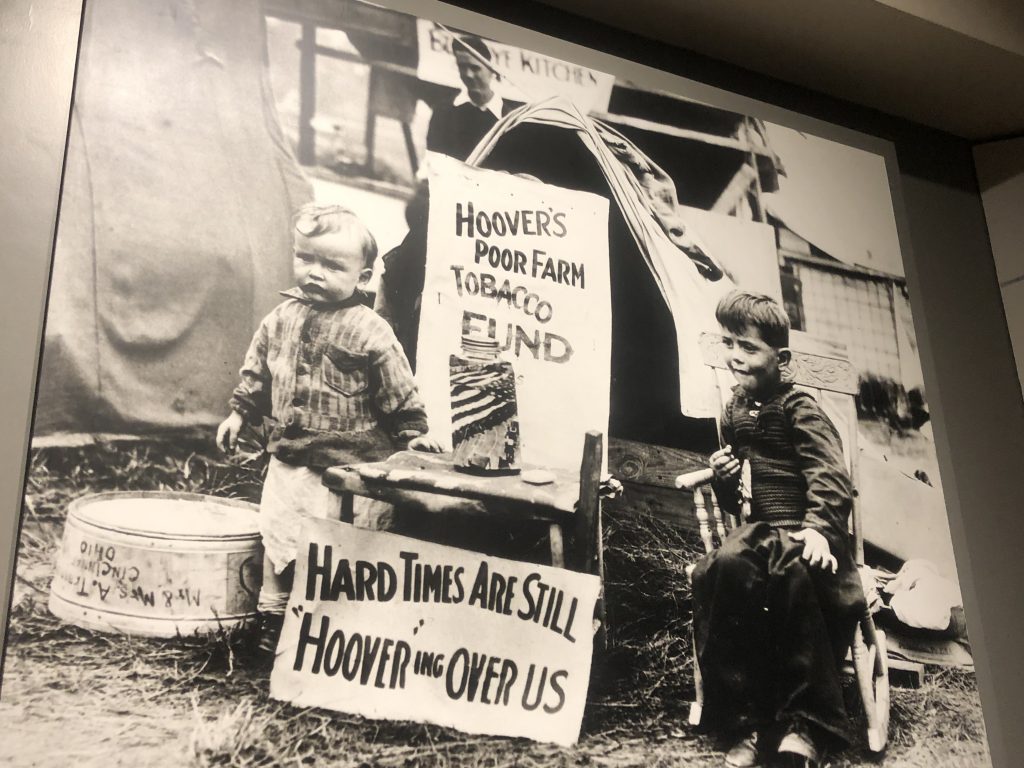

Hoover museum artifact.

And the museum’s text reflects, “Hoover’s presidency showed the limitations of managerial government in a time of national emergency. With his stiff-necked refusal to play the political game, the president clung to the same theories of individual initiative and grassroots cooperation that had fed war-torn Europe and ministered to flood victims in this country.” The museum displays pictures of hungry Americans and the famed “Hoovervilles” filled with despair.

A president with a newspaper!

Hoover was one of the biggest baseball fans of all American presidents. He threw out the traditional opening day first pitch at all four Washington Senators’ opening days while he was in office.

He also attended the fifth and final game of the 1929 World Series between the Cubs and the Athletics in Philadelphia. The museum shop sells Hoover baseballs and a cardboard plaque with his 1955 observation that “Next to religion, baseball has had a greater impact on our American way of life than any other American institution.”

Hoover built a fishing camp in the Blue Ridge Mountains where he would also meet with economic advisors. The museum features a mannequin of Hoover fishing while wearing a tie and fedora. Hoover was one of two American presidents to give away his salary. John Fitzgerald Kennedy was the other. These days I like learning about good news.

A well-dressed president keeps his head above water. (D. Hoekstra photo.)

The parallel subtext of the Cash exhibit is the possible redemption of a president. When looked at in totality, Hoover doesn’t seem like a total loser. Especially after the trauma we went through between 2017 and 2021. Glen Jeansonne’s 2016 biography “Herbert Hoover: A Life” recalibrates Hoover’s image with a progressive spin.

Cash sang the Sheryl Crow ballad “Redemption Day” on his posthumous 2010 “American VI: Ain’t No Grave” album. His life had bottomed out in 1968. He was addicted to pills (as seen in the documentary) his personal life was off the rails (he would marry June Carter in March 1968) and Columbia Records threatened to drop him.

The Folsom Prison project changed the trajectory of his career. The “Johnny Cash at Folsom Prison” album sold more than 3 million copies. (The late San Francisco rock photographer Jim Marshall also made some images of the concert.) The 1969 follow-up “At San Quentin” hit number one on Billboard’s pop and country charts and delivered the Grammy-winning single “A Boy Named Sue,” written by Chicagoan Shel Silverstein.

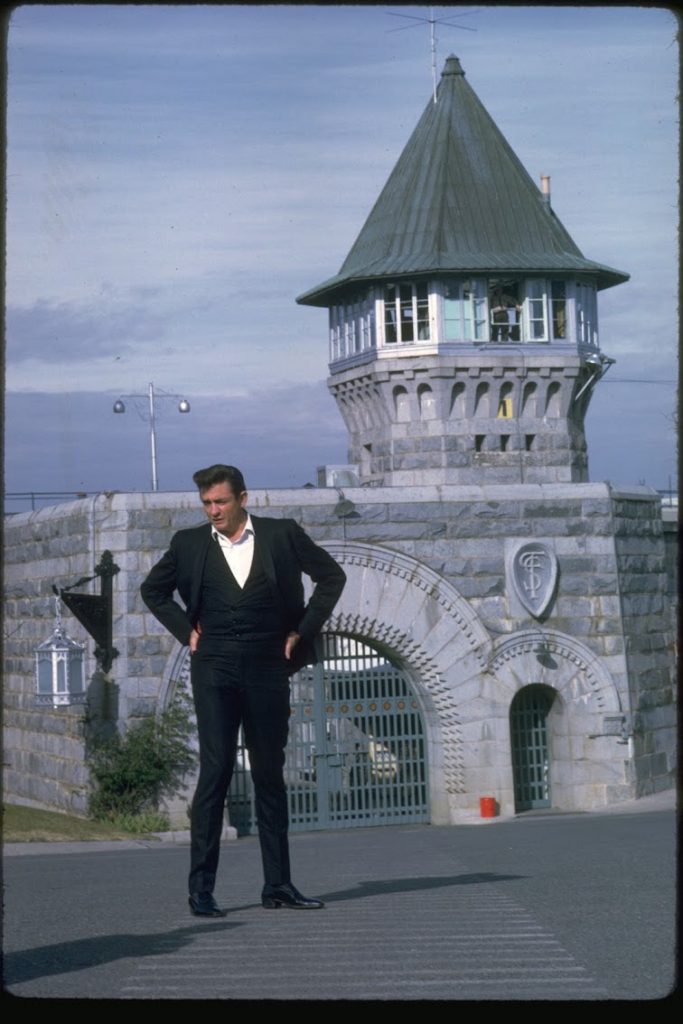

Cash outside the East Gate of Folsom Prison, 1968. (Dan Poush photograph courtesy of Herbert Hoover Presidential Museum.)

For the rest of his life, Cash became an advocate for prison reform–just like Hoover. Cash, who died in 2003, was concerned about how first-time offenders could be incarcerated with hardened criminals. He did not see much redemption in the system. In July 1972 Cash testified before the Senate Judiciary Committee’s subcommittee on national penitentiaries.

In one more coincidence, Cash was born in 1932—the final year of Hoover’s term as president. Unemployment was 25 percent. That can lead to some serious crimes.

In the spring of 1933, a broken-down Hoover and his wife left the Waldorf in New York City for Palo Alto, Ca. on one of the trains that Cash would later sing about. Within the extended rhythm of redemption, one chapter of American history was closing as another one was being born.

Leave a Response