Tony Fitzpatrick; A baseball road trip and a lucky tattoo

Tony, for my 2000 road compilation “Ticket to Everywhere.” He titled the book.

In early 1992, I took a road trip with artist-writer-friend Tony Fitzpatrick to Kansas City, Mo.

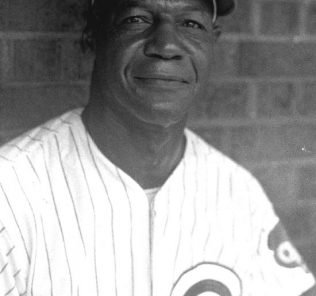

The weekend was covered by a grainy mist, but it did not compromise the light we discovered. Tony was making birch wood baseball cards .I wanted him to meet Buck O’Neil, the Negro League legend who in 1962 became the first on-field Black coach in MLB history when he was hired by the Cubs.

One evening, Tony and I went out for dinner in the Westport neighborhood. I knew of a good dive bar, but Tony did not drink. He walked back to the hotel. I had a beer, and when I returned, he mentioned the same joint I had visited without knowing I had gone there. We both loved the promise of neon.

That’s what was so wonderful about Tony.

He found his own path, and it always took him home.

O’Neil’s house was about two miles from where he played and managed the Kansas City Monarchs baseball team in the Negro Leagues. He greeted us on a Saturday morning in a natty blue suit and matching tie. He had just turned 80. Tony was 33. He died of heart failure at the age of 66 on Oct.11.

Tony’s artistic pursuits were constantly evolving and blossoming. In the late 1980s and early ‘90s his catalog included underbelly characters like mass murderers, boxers, and porno queens.

He contributed art to the 1986 Jonathan Demme film “Something Wild” (in which his radio pal Buzz Kilman played a television newscaster.) His colorful baseball “cards” were a mood departure. They were a bit larger than pulp paperbacks, and they included Roberto Clemente, White Sox great Luis Aparicio and Pete Rose.

A few weeks after our visit, on Feb. 9, 1992 Tony and his wife Michele had their first child, Max. (Their daughter Gaby was born on Nov. 5, 1994.)

“Becoming a father had a lot to do with how happy these are,” Tony told me in ‘92 while looking at his Satchel Paige slate. “Until this, my paintings have been pretty much dour. These are paintings of joy. They are about the best time of my life. They are painting that maybe my son would like. I had a wonderful childhood.

“I had baseball.”

Buck always had words of wisdom.

On that cloudy morning, he told us, “Segregation was a terrible thing, but it did one good thing. We had to own a lot of things we don’t own now. We had to own our own grocery stores, hotels and restaurants. That’s all changed. The big corporations took all that. There was no way a small, family run hotel could compete with a corporate hotel. So they went out of business. The same thing happened with the Kansas City Monarchs, the Chicago American Giants. They were making money.”

Tony later said, “Buck dispelled a lot of fashionable thinking I had. The Negro Leagues were not a second-class league. It was a great league. So I didn’t paint somber, righteously white guy-liberal angry paintings. I wanted to make paintings that celebrated these guys and their lives.”

Tony honored such independence and proprietorship throughout his career.

After a 1994 boxing-themed group show with artists Ed Paschke and Wesley Kimler at Tony’s World Tattoo Gallery on South Wabash Tony told me, “We’re trying to send a message to younger artists that if you expect to survive, your art better be about ideas and you better take control of your career.” Tony even snagged the Bigsby & Kruthers men’s clothier to sponsor the boxing show that on opening night featured one of the early-era appearances from the Waco Brothers.

Tony was self-made which begins to explain his hustle and swagger. I called him a raconteur which he cheerfully translated into bullshitter. He really knew how to work the media. Tony was committed to the experience.

His father James Fitzpatrick drove around Chicago selling burial vaults, embalming fluid and insurance. He died in 1998 at the age of 73. Many times he would take Tony along on his route. “One time I had gotten the boot from grade school,” Tony told me in ‘99. “It was a treat for me to go to work with my dad, so I’d do things intentionally to get kicked out. Knock desks over. Screw up phonics.”

James was born in 1925 in St. Anthony’s Hospital, 2875 W. 19th. His future bride, Annamae, was born six hours later in the same hospital. Their mothers met in the maternity ward and stayed in touch over the years. Annamae and James married in 1948. The Fitzpatricks lived in Chicago until the late 1950s when they moved with their three children to west suburban Lombard. Tony was on the way! (The Fitzpatricks had eight children.)

Early in Tony’s career Annamae would buy chalk slates at a dollar a piece for his art at a Lombard paint shop. She died in 2016 at the age of 91. Visitation was held during a Cubs World Series game so the calling hours ended at 7:07 p.m., just before first pitch.

Tony was born at Evangelical Hospital, 5421 S. Morgan in Chicago and came home to Lombard. Jean Motier, his father’s male cousin by marriage delivered all eight Fitzpatrick children. Once the Fitzpatricks settled in Lombard James began commuting to Chicago, typically in a huge champagne-green Oldsmobile, about the size of a Riverview carousel.

This was the origin of Tony’s love of Chicago. His father knew the history of every neighborhood. “We couldn’t go down Western Avenue without hearing about the world’s largest street car line,” Tony said. “He knew the flower shop across from Holy Name Cathedral where (mobster Dion) O’Banion got hit. We’d stop at something like 30 funeral homes. He had matches and calendars to give out to those guys. He used to tell people cremation was a sin against God,” and Tony laughed.

“…….Because he sold burial vaults!”

Being exposed to death at a young age shaped Tony’s empathy. I’ll never forget how he showed up at both of my parent’s funerals, held six weeks apart in Naperville. My father was also born in Chicago, and like James, he embraced the boulevards of his youth. There is new light when children discover the pathways of their elders.

Me and Tony at my 2018 housewarming. That’s his heart up over his right shoulder.

I met Tony in 1985 when his studio was in a storefront in the shadow of the Ovaltine factory in downtown Villa Park.

I was doing a Sun-Times profile and we discovered we had many things in common:

West suburban roots, lack of a college degree, short attention spans, love of baseball, love of the Neville Brothers, love of the Cock Robin hamburger, affinity for late nights and more.

In 1977 Tony graduated from Montini Catholic High School in Lombard in where he flunked art. He preferred to draw sketches of Jimi Hendrix. He became a bouncer, bartender and busboy at the TGI Friday’s on the border of Lombard and Downers Grove where he worked with our friend Mark Ibach, who died in May.

In 1993 Tony designed a 1950’s style “Lucky Kind” tattoo for me. I was in a bad streak. His design features a panther crawling up a playing card. A pair of dice are rolling sevens above the card. Tony and I went to Bob Oslon’s Custom Tattoo, 3817 N. Lincoln Ave. Bulls Hall of Famer Scottie Pippen had his “PIP” tattoo done here. Artist Scott Harrison spent 90 minutes applying the “Lucky Kind” on my upper right arm. Tony sat and watched.

He liked it so much he then had Scott give him the same tattoo but with flames emerging from the card. (It was Tony’s fourth tattoo.) Tony’s brother Kevin said the idea might have seemed spontaneous, but it was a way of sharing our lives and destinations for a very long time.

Lucky Kind, left shoulder.

So we were kind of Lucky Kind brothers.

One difference between me and Tony is that I was generally reserved. Tony’s ebullient nature manifested itself in his uncompromising benevolence. He loved life. He did a lot for me with no receipts. He hosted a couple of book release parties. He did book covers. He was the emcee for our “Center of Nowhere” documentary screening at the Music Box, he provided his bird art as the wrap for the Ford Transit van I bought for “The Camper Book.” He believed in me.

He was generous to all my friends and family. My mom always asked, “How is that Tony Fitzpatrick doing?” His kindness made an impression. That is what I will always remember.

In 1993 I had an assignment to interview former Latin King member Hector Maisonet at Stateville in Joliet. He was the star of the Stateville Correctional Art Program. Four of his pieces were discovered by the Carl Hammer Gallery. Unfortunately, Hector was doing time for armed robbery in a gang shootout in Humboldt Park. He also had been transferred to Stateville from Pontiac for participating in a prison riot. I brought along Tony.

Hector told us he had never been to an art gallery and that was one of the first things he wanted to do when he was released. Tony insisted we make a return trip so he could give Hector some paint and brushes. Years ago I heard Hector got out, only to return to jail for holding up a convenience store. But Tony always believed the power of redemption.

During our time in Kansas City, Tony and I ate at Arthur Bryant’s Barbeque, and we found the gravesite of the legendary Negro League pitcher Satchel Paige at Forest Hill Cemetery. The headstone features Paige’s six tips on “How To Stay Young,” with the last one saying, “Don’t look back, something might be gaining on you.”

Tony Fitzpatrick stood tall ahead of the pack. He always looked ahead, seeing possibilities from the smallest bird to the largest dog. He witnessed potential in strangers and beauty in his neighbors. He had no patience for borders and dress codes. He rolled up his sleeves in tough times. He was everything Chicago aspires to be.

Well written story, never knew Tony but this road trip explains his open minded approach in his paintings.

Heard old interview today on WGN Bob Sirott show. Both big Cub fans.

What an amazing life.

Thank you, Don for reading and writing…Tony loved the White Sox as well.

I never knew about those baseball cards Tony made. Really cool.

Thanks, Kevin.

Good story, Dave

Rich

Thanks, Rich!