The New Kansas City Monarchs

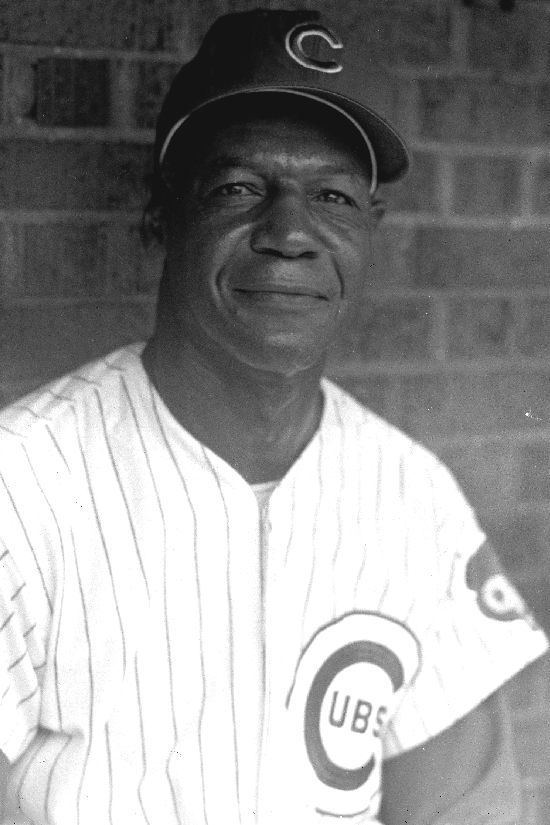

The late Buck O’Neil visits his Monarchs with a rainbow on opening day 2021 (Courtesy of Kansas City Monarchs.)

KANSAS CITY, KS.—The Kansas City Monarchs were the royalty of baseball’s Negro Leagues. They played in Kansas City, Mo. between 1920 and 1961 and their graduates included Hall of Famers Jackie Robinson (1945), Ernie Banks (1950-53), and Satchel Paige (1934 and 1940-47). The team produced more major league players than any other Negro League franchise.

The Monarchs have taken a new flight as a member of the American Association.

These Monarchs play at Legends Field in Kansas City, Ks. They were previously the Kansas City T-Bones in the independent league American Association. The rebranding is the result of an unprecedented collaboration with the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum (NLBM) in Kansas City, Mo.

I visited the Kansas City Monarchs during their first homestand in mid-May. I also visited the NLBM before the game. It is a 22-minute drive between the museum and the Field of Legends, a necessary double-header.

The Field of Legends is adjacent to a huge, modern shopping mall called Legends Outlets. If your significant other doesn’t care for baseball, they can visit Banana Republic, a Beef Jerky store, a VANS outlet, an AMC theater, and more. The ballpark is also across the highway from the Kansas Speedway.

This is a different world from the NLBM at the urban corner of 18th and Vine. From the 1920s through the 1930s more than 200 jazz clubs existed in Kansas City, Mo., and 18th and Vine was ground zero.

Chicago American Giants pitcher (and owner) Rube Foster founded the Negro Leagues the Paseo YMCA, two blocks from the museum. Today, the historic neighborhood is struggling to hit all the right commercial notes.

On the drive over to Kansas City, Ks. (pop. 152,000), I thought of the Negro League legend Buck O’ Neil (1911-2006). I visited with Buck a couple of times at his home in Kansas City, Mo. In 1995 I drove to Kansas City, Mo. for a “Soul of Baseball” celebration at the Art Deco Town Pavilion. There were 222 of 250 surviving Negro League ballplayers in attendance. It was the largest reunion of these ballplayers that ever took place. Buck was chairman of the museum.

Buck O’Neil was a Cubs coach in 1962 and he signed Lou Brock. He should be in the Baseball Hall of Fame.

“Can’t you see this love emanating from my heart to you?” asked Buck, then 83. “Isn’t it wonderful that people are actually recognizing the men who built the bridge, not only men who crossed the bridge?” With his voice rising to the forgiving Missouri skies Buck then asked all the players to stand up. Many laid down their canes.

I remember Chicagoan Ted “Double Duty” Radciffe wrapping his knobby fingers around the steel arms of his wheelchair. He was 93 years old. He braced himself and slowly rose.

He was recognized.

That’s what this road trip is all about.

The new Monarchs were created as a collaboration between new team owner Mark Brandmeyer and NLBM President Bob Kendrick. Brandmeyer, 61, is co-owner of Built Interior Construction in Kansas City, Mo. and he’s involved with three medical device companies, one of which is hospice care.

“This came across my desk,” Brandmeyer said in an early June phone conversation. “I’ve always been interested in sports. Initially, I said ‘No.’ The brand was kind of beat up and it’s a lot more complicated of a business than it appears. You’ve got food and beverage. Merchandise. Sponsorships. And then putting a team on the field. I thought it would be more work than I wanted to get involved with.”

In early 2019, Kansas City, Ks. mayor David Alvey called Brandmeyer with a nudge. “He said our group was the furthest along and if we didn’t do something we would probably lose the team,” Brandmeyer recalled.

“That was painful. Sports teams make up the fabric of our society. I think back to when Kansas City lost the Kansas City (now the NBA’s Sacramento) Kings. There were so many great players and they were influential with the youth in Kansas City. So I thought if I just get in and run this a little bit better and it just breaks even, at least I’ve done something good for Wyandotte County.”

Legends Field in Kansas City, Ks. 2021. (Courtesy of Kansas City Monarchs.)

Then, the world was hit with a pandemic.

“Nobody expected that,” he said. “There were times I thought, ‘Should I take my lumps and move on to another deal?’ But we got through it. We had the Royals farm clubs playing there. Also during that time, the idea came to rename the team. I called Bob Kendrick and initially, he was hesitant to do anything with the Monarchs name. We agreed that the Monarchs is a great legacy brand. But you can only tell the story so many times. Now that brand lives on. It becomes a megaphone for the museum to tell all the great Negro League baseball stories, but also create a future for Kansas City.”

The Field of Legends (capacity 6,537) is 17 years old. Bathrooms and suites have been refurbished. The stadium features eight lightboxes and four locker box displays honoring Negro League legends like Buck O’Neil, Cool Papa Bell, and others. I bought a commemorative felt Monarchs pennant where proceeds help support a local Rotary Youth Camp.

I met throwback entertainers Yoga Berry and L. Bambino. The men were dressed in 1920s baseball uniforms and I admired their juggling during a rain delay. The previous day, on the Monarchs home opener, a dramatic rainbow emerged over right field. Everyone attributed that moment to Buck O’ Neil.

Yoga Berry and L. Bambino–my new friends at Legends Field.

Players are not issued the numbers 5, 22, and 25, the numbers that Jackie Robinson, Buck, and Satchel Paige wore for the Monarchs. The Monarchs plan to host a formal number retiring ceremony. “

We took the players to the Negro League Museum,” Brandmeyer said. “A lot of the Black and Brown players stand on the shoulders of the players that went before them. They take that to heart.”

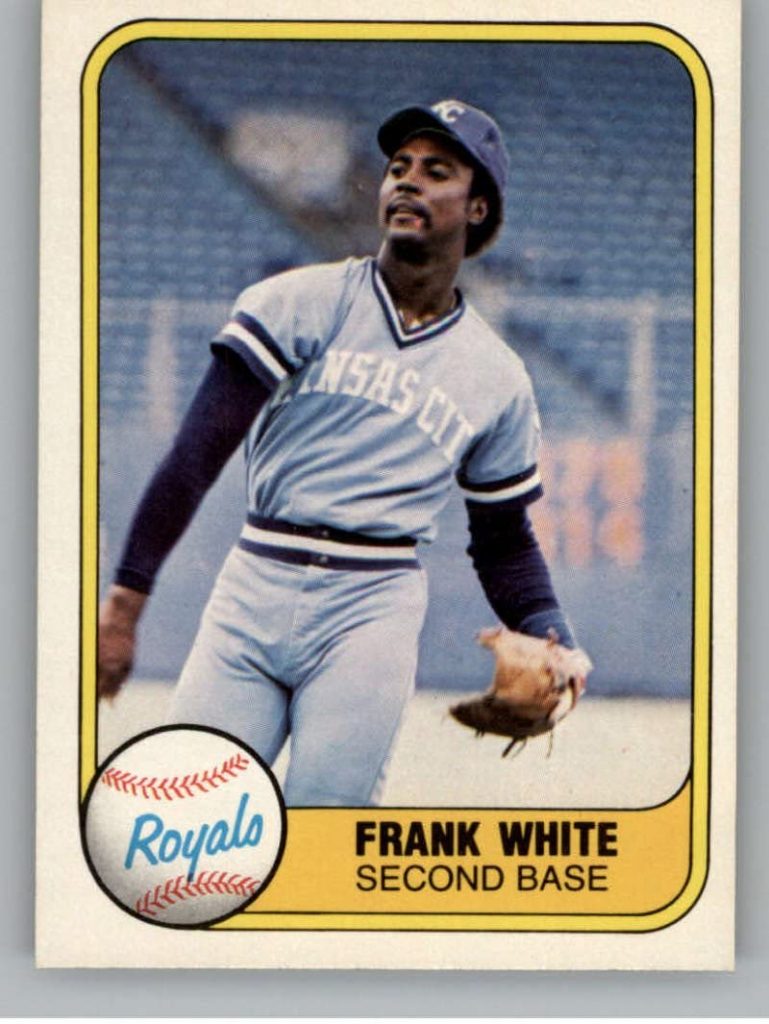

Former Kansas City Royals all-star shortstop Frank White is the Monarch’s first base coach. Despite the gloomy weather, White cheerfully tossed a couple of balls to fans along the first base side of the stadium. He is also county executive for the Jackson County (Mo.) Legislature. White has been with the Kansas City independent league team for ten years going back to the T-Bones. He does not travel with the team.

“I was doing broadcasting for the Royals until I parted ways with them in 2011,” White said in an early June phone conversation. “The T-Bones asked me to come over. I was still interested in teaching baseball. Some of these guys have touched the major leagues a bit. Some players want to work themselves up. Some have had injuries, some weren’t mature enough, sometimes teams give up on you a little too fast.”

White’s number 20 has been retired by the Royals. But his split with the Royals was a little messy as detailed in his 2012 autobiography “One Man’s Dream: My Town, My Team, My Time.” After playing and coaching for the Royals, White was mentioned as a candidate to succeed Royals manager Buddy Bell after the 2007 season. He was passed over for Trey Hillman and White resigned from the Royals front office in 2011.

White is one of 14 MLB players who came through the Royals Baseball Academy that operated between 1969 and 1974 in Sarasota, Fla.

White will be able to shine a light on the Monarchs Youth Academy that will enrich the lives of Kansas young people through baseball and softball.

Brandmeyer said, “It will be a complement to the Royals urban youth academy. It would be more focused on Wyandotte County. The Royals focus on Kansas City, Missouri but they don’t focus as much on Kansas City, Kansas. This will also be a career development program with a curriculum to teach the business of sports, whether it be field management, sales, and marketing, food and beverage or broadcasting.” Brandmeyer said the academy will be built near the Monarchs stadium.

White explained, “For me, the academy was a vehicle to understand the game a lot better. It gave me an opportunity to work every day on fundamentals. I take that with me today. I ask what are the fundamentals and opportunities in this challenge? To give you a good idea, I came from no-high school baseball to 30 games a summer. I was 20 years old when I came into the academy and by 23 I was in the big leagues.” White went on to play in 2,324 games over an 18-year career.

Brandmeyer added, “We are so lucky to have Frank White. He’s an eight-time gold glove winner and he has a full-time job. We do pay him, but not much, to be our first base coach. He really does it for the love of the game. He could do a lot of other things but he chooses to do this.”

White and Brandmeyer took the Monarchs to Monarch Plaza, 22nd and Brooklyn in Kansas City, Mo. The plaza is the site of the former Municipal Stadium where the Monarchs played between 1923 and 1954 and was also home to the old American Association’s Kansas City Blues.

“My high school was on the west side of the stadium,” White said. “I told them about the area, about the team, the stadium. From there they went to the museum. I was part of the original group in 1990 that got together to discuss the establishment of a museum. I was there with Buck O’Neil, (former Monarch-Detroit Stars outfielder) Slick Surratt, Connie Johnson (Monarchs and Chicago White Sox pitcher), and more. It was neat to see it come to fruition. The players enjoyed it.”

Negro Leagues Baseball Museum (Provided photo.)

The Monarchs are under the umbrella of Brandmeyer’s new company MaxFun. The company’s ultimate goal is to create a diverse brand. “We hope to buy other teams or other entertainment opportunities,” said Brandmeyer, a native of Kansas City, Mo. “We’re looking at adding a pickleball court and an outdoor music stage. We have about three acres in the back of the stadium that we’re looking to program to help make it a 365-days-a-year venue. Although we’re not connected with Legends (mall) business-wise from a legal standpoint we pull for each other. We’re having an open house on our next homestand where we’ve invited ten of the closest apartment complexes to join us for a game. Our philosophy is a rising tide raises all ships.”

White said, “The Monarchs name is repeated a lot. People are wearing the apparel. I see diversity in the crowd at the games. This is different and this is history.”

I thought about entrepreneurial equity as I moved from the NLBM to the Field of Legends. The 18th and Vine District has a couple of independent restaurants but nothing with the depth of the Legends Mall. The restored Gem Theatre, 1616 E. 18th St. (built in 1912) is used for events at the American Jazz Museum. The jazz museum shares the space with the NLBM, although there are separate admissions.

“Economic equity is more of a city issue,” White said. “I’m the head guy of our county. But there’s been a lot of effort to build up that area (by the NLBM.) Businesses don’t last long. That could be for a lot of reasons. Maybe the rent is too high. Or maybe there’s not enough foot traffic. From a crime standpoint, sometimes things happen there. They continue to try to build up that area with the Buck O’Neil Education Center they’re working on (in the old Paseo YMCA) and the museum itself. But you have to have a significant investment to get it the way it needs to be.”

There is business equity at the Monarchs stadium. It was a delight to meet Mary “Shorty” Jones, co-owner of Jones BBQ in Kansas City, Ks. (Locals claim the better barbecue is on the Kansas side.) Jones’s concession stand is in the plaza as you enter the stadium. She runs Jones BBQ with her sister Deborah “Little” Jones. They received national notoriety in 2018 when the “Queer Eye” television show did a makeover of their restaurant.

The stadium’s pulled pork sandwich was accented with a feisty tomato-based sauce and a dash of celery. Shorty had a big personality and I’ll remember her as the first woman who has flirted with me in seven years.

Kansas City, Ks. pitmaster Mary “Shorty” Jones. (D. Hoekstra photo,)

White is a great beacon of hope for the new Monarchs. “I grew up on the east side of Kansas City where the museum is,” he said. “Back in 1968 when I came out of school there (the all-Black Lincoln High that included jazz great Charlie Parker and barbecue king Ollie Gates as students) were riots right after Martin Luther King was assassinated. A lot of that area burned down and it just hasn’t recovered. My focus has always been on how to get involved and how you can affect people’s lives. That’s the reason I got into politics. I wanted to see if I could make a difference.”

And now, the Kansas City Monarchs are making a difference in America’s baseball landscape.

Wonderful article, Dave. In the article you mentioned the great jazz tradition KC once had. Years ago I learned KC once had. Do you know if there are any remnants still chugging along?

Thank you and good question. There is a jazz museum across the hall from the Negro League Baseball Museum (separate admission), but I did not see any late night/evening jazz clubs in the area. There’s a couple of restaurants.

Great article. A nice look at what was and what could be.

Thanks for reading and writing, Bill.