Sputnik Monroe’s Memphis

Monday, August 31, 2009

Monday, August 31, 2009

The recent death of Jim Dickinson got me to thinking about the late Sputnik Monroe. This is a piece I wrote a couple of years ago that kicked around Sports Illustrated for a bit before getting kicked back to me.

Jim and Sputnik are kindred spirits spinning around the earth.

BY DAVE HOEKSTRA

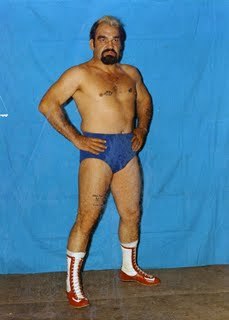

Sputnik Monroe was a satellite of a man who saw a planet big enough for all walks of life. The rock n’ roll wrestler was born in 1928 as Roscoe Brumbaugh on the plains of Dodge City, Ks. He came of age in the restless humidity of Memphis, Tn. He died in November, 2006 in the cradle of promise called Florida. He never backed off from the heat.

Monroe was one of the underchampioned figures of the civil rights movement. During the late 1950s he played to the segragated black balcony of Ellis Auditorium, about 10 blocks from the then all-black Beale Street entertainment district in downtown Memphis.

Monroe was nicknamed after Sputnik, the first artifical satellite that was launched on Oct. 4, 1957. He was an ambassador of soul, a liberating, pompadured potion in motion. He wrestled with a flamboyant white streak shooting like a lightning bolt down the middle of his jet black hair. The Valley of Elvis Presley could relate. Monroe was takin’ care of business.

Long-time Memphian Jim Dickinson played piano on Bob Dylan’s Grammy-winning “Time Out of Mind” album and in 1971 brought the Rolling Stones to Muscle Shoals, Ala. to record “Sticky Fingers.” Dickinson is a wrestling fan. A black and white picture of Monroe’s successor Jerry “The King” Lawler hangs in Dickinson’s trailer on his North Mississippi compound.

“Sputnik Monroe integrated the Memphis audience,” Dickinson said while sitting among his collection of Larry Brown books in his trailer. “Absoultely. He’d go on stage, radio shows, television shows, anywhere he could find an audience he would work it. And what is Memphis about? Music, race and Elvis. And Sputnik went for it all.”

Memphis has always been about big ideas. Holiday Inn started in Memphis. So did Federal Express and the Piggly Wiggly grocery chain. But Monroe referred to other Memphians as “liver-lipped little pukes.” He played the role of the heel with all his foot stompin’ heart. He snarled like a Delta catfish and swayed like a Baptist choir. Monroe was generally booed by ringside whites and cheered by blacks. His friends included the late Sam Phillips, who discovered Presley and started the legendary Sun Records. Monroe became an icon for many teenage white boys growing up in Memphis as rebellion was being fused into rock n’ roll.

Monroe’s gold jacket, lime green tights and wrestling boots are on display along with items from Presley, Otis Redding and Isaac Hayes at the Rock n’ Soul Museum a half block south of Beale Street. There’s also a menu from a late 1950s Beale Street diner that offered “Sputnik’s Breakfast Special” (choice of chilled juices, two fresh ranch eggs to order, U.S. Choice minute steak, choice of hash brown or French Fried potatoes, hot biscuits and butter and choice of beverage: $1.35.) A plaque honoring Monroe adds, “He often strutted down Beale Street, he trangressed the color line and encouraged his African-American friends to violate segregation ordinances. He became so popular at Ellis Auditorium that the balcony seating could not accomodate all his African-American fans…..Sputnik Monroe played a major part in destroying the color lines in Memphis entertainment venues.” After Monroe’s death The Charleston (S.C.) Post and Courier wrote, “He just may have been the most improbable civil rights hero the South has ever seen.”

Monroe died on Nov. 3, 2006 in an Edgewater, Fla. nursing home after a long battle with lung cancer, prostate cancer and respiratory ailments. The old wrestler had run out of moves. In 2005 Monroe and his wife Joanne had moved to Flordia from Katy, Tx. She was the last of Monroe’s six wives. In the spring of 2004 Monroe gave one of the last accounts of his colorful life.

He was living in a modest ranch house in suburban Houston. His kitchen table was filled with medicine bottles, pills and MRI charts. Monroe wore a red tee shirt from a local hospital. Both his arms had tattoos he got in 1945, his first year in the U.S. Navy. He wore white shorts and black socks. He threw soft punches into ghosts that drifted in the humid air.

“Its hard to be humble when you’re 235 pounds of twisted steel and sex appeal with the body women love and men fear,” Monroe said as he echoed a long ago tag line. His words rang through the quiet house. Monroe moved to Houston in 1980 to cash in on the oil boom. It didn’t work out. He was a shuttle bus driver for a rental car compay at the airport. He became a security guard at a Holiday Inn. [Sam Phillips was one of the original Holiday Inn stockholders.] On his way to the Holiday Inn Monroe met Joanne while she was wrapping hot dog buns at a Stop n’ Go in Houston. They married in 1994. Monroe’s 46-year-old son once wrestled around Houston as Bubba the Brawler. Monroe’s 48-year-old daughter Natalie is a nurse who lives in Arizona. Another son, Allen, was unknown until he appeared at Monroe’s funeral where he performed a Native American chant. In Texas, Joanne had been a sales associate at a local Wal-Mart. She had broken her ankle and was out of work. “We were both sitting here with no income,” Monroe said as he took a long drag from a Marlboro Light 100. “Knox and Jerry (Sam Phillips’ sons in Memphis) came to the rescue.”

Monroe was breaking down barriers in sports just as Sun Records was breaking down barriers in music. For a spell he wrestled as Elvis ‘Rock’ Monroe. He carried a guitar into the ring and proceeded to get whacked around with his own guitar. Monroe cut a novelty single “Man, That’s the South” for Satellite Records in Memphis. Satellite was the precursor to Stax Records. In 2003 a Los Angeles alternative rock band named itself Sputnik Monroe. The drummer wore a black Mohawk.

Jerry Phillips said, “He was as rock n’ roll as any artist at Sun. His persona was one of rebelliousness and rock n’ roll is a good term for rebellion. He was every bit the showman Elvis and Jerry Lee Lewis were. Sometimes he would knock the hell out of somebody when he wasn’t supposed to, just to get the crowd going.” Phillips said that Monroe hung out in the Sun Records studio with his father and the seminal Sun artists of the late 1950s that included Lewis and blues great Junior Parker.

Knox Phillips added, “Sputnik embodied the spirit of independence which is what made him such a star in Memphis.

Musically, Memphis is the home of the independent spirit. Sam (Phillips) laid that groundwork. Sputnik was the same way. He struck out on his own racially by appealing to blacks as his brothers. Sputnik would walk down the middle of Beale Street and raise up his arms. People would chant, ‘Sputnik! Sputnik!’ He was the craziest of the crazies in wrestling, which is saying a lot. He desegragated Ellis Auditorium. He was as unreal as the satellite was in those days.”

Ellis Auditorium was the site of Elvis Presley’s first sold out concert. Built in 1924, the auditorium was a primitive setting for a sports event, which only enhanced Monroe’s dramatics. The ring was in the center of the dark, cavernous building. A singular spotlight hit the stage and Monroe would explode out of the glow with the attitude and anger that was supressed in his black following. Nearly 100 seats were reserved for blacks in the distant balcony, an area lined with velvet drapes which locals called “The Crow’s Nest.”

Monroe recalled, ” I told the auditorium manager that if he didn’t make room for my black friends, I’m outta here. I didn’t bullshit around. I meant what I said. The south side of the stage on the floor held 1,000 people. That became black, too.” Monroe instructed ticket takers to sell tickets after the balcony sold out and white only seats were available. “I’d give the ticket man $20 and tell him to let it roll for a while,” he said. “Everybody’s got a price.” Once the auditorium was integrated, promoters saw an increase in profits. Memphis nightclubs soon followed the lead of the Ellis Auditorium. Another time black leaders in Memphis were protesting against the segregation of an automobile exhibition. Monroe got on the phone and told the sponsors he was going to open his own auto show in all-black northern Mississippi. That night, the Memphis dealers announced a change of admission policy on the local news. One time Jerry Phillips was walking down Beale Street with Monroe. Phillips said, “A kid came up to him and said he was raised with pictures of John F. Kennedy, Martin Luther King and Sputnik on the wall.”

In the early 1970s Monroe wrestled with Norvell Austin, a black tag team partner. After they defeated an opponent—-usually white—-Monroe dumped a can of black paint on the loser and screamed, “Black is beautiful!” Austin would scream back, “White is beautiful!” Then in tandem, Monroe and Austin would shout, “Black and White together is beautiful.” This was long before Stevie Wonder and Paul McCartney. Monroe palled around with black cooks at the historic Rendezvous restaurant in downtown Memphis. He liked to find the most gangly help and encourage them to put him in a headlock. Monroe wore fancy threads and gaudy belts from Lansky Brothers on Beale Street (where Presley also shopped). Monroe’s ability to build bridges earned him a chapter in the 2004 Juan Williams book “My Soul Looks Back in Wonder: Voices of the Civil Rights Experience.” Music writer Robert Gordon also devotes several pages to Monroe in his book “It Came From Memphis.”

Monroe’s grandfather was a horse trader and a bare knuckled fighter. Monroe’s father Roscoe Monroe was killed in a 1928 plane crash two months before he was born. When Monroe was four his mother Ruie Avelina married his stepfather Virgil, a superintendent of the Miller & Smith bakery in Dodge City, Ks. “One time I walked to the bakery to take his dinner to him in a sack,” Monroe recalled. “I got lost in a duststorm. The dust was so bad, you couldn’t recognize the streets.” The family moved to Wichita, Ks. where Monroe began wrestling at East High School and the family continued to operate a bakery. He said, “I helped in the bakeries and there was always at least two blacks in my stepfather’s crew. Sometimes they’d help me with the big mixers. I’d have to get inside of them to scrape them down and clean them up. I didn’t see any difference between them and the other help.” After serving in the U.S. Navy between 1945 and 1947, Monroe saved $3,000

and bought his own bakery in Anthony, Ks. It didn’t work out either.

But Monroe paid attention to the carnival circuit that rolled through town during long summers in the plains. One carnival headliner was a wrestler who took on anyone in the audience. Monroe accepted the challenge, won and joined the carnival. He started wrestling as a junior heavyweight (218 pounds). “You had five minutes to beat a guy,” he recalled. “If you didn’t beat him, you threw your stuff in a suitcase and went down the road.” Monroe spent the early 1950s wrestling in carnivals in small towns throughout the heartland. He once purchased a cape from Mel Peters, who was a knockoff of Gorgeuous George. “It was an outstanding gold cape,” Monroe said. “I wore it on the bally platform in front of an athletic show in Nebraska. They started a chant, ‘Pretty Boy’ ‘Pretty Boy’ like I was gay or something. But what became ‘Pretty Boy Rocque’ (a spinoff of his given name Roscoe or ‘Rock’) stuck. Its strange about my names.” Its more strange that Pretty Boy’s get up also included pink shoes and sequined robes.

In the fall of 1957 Monroe was driving long shifts on a road trip from Washington to a televised match in Mobile. Ala. All the highways were two lane, north and south. “When I got to Greenwood, Mississippi I spotted a little black guy hitchiking,” Monore said. “I asked him if he could drive to Mobile. When we got to the arena I went through the crowd with my arm around him. He was carrying my bag. An old lady was cursing and raising hell. Security said if she didn’t stop swearing they were going to have to put her out. Then she shouted that I wasn’t “nothing but a Goddamn Sputnik!’ I didn’t know what a Sputink was. I had no idea. Two or three days prior to that is when the Russians sent Sputnik (I, the manmade satellite) up. But everybody picked up on it. The commentators started calling me ‘Sputink’. And it stuck.”

After stops in St. Louis and Louisville, Monroe landed in Memphis in 1957. He quickly made a name for himself. Just to get attention, he laid down on a blanket at the intersection of Union and Main in downtown Memphis. He stopped traffic and six policemen were dispatched to the scene. “I said I was capable of kicking six policemen’s ass,” Monroe boasted in a hoarse whisper. “They came back with 12 and took me to jail.” Monroe was arrested on Beale Street for “Mopery and Attempted Gawk.” Monroe whistled and said, “So I got a black lawyer. That really went over. I told them I was a Navy veteran so I thought I could go anywhere in the United States, whether the neighborhood was black or not. They threw out my case. I didn’t have any more trouble after that. They accepted my excursions on Beale Street.”

Monroe’s black lawyer was Russell B. Sugarmon, Jr. a civil rights attorney who went on to become a Memphis judge. In 1959 he became the first African-American since the Civil War to make a bid for a major city office in Memphis when he ran for public works commissioner. He lost. “Wrestling matches desgragated Memphis,” said Judge Sugarmon, who retired earlier this year. “There was a legitimate theater called the Front Street Theater. My wife and another lawyer’s wife bought season tickets. One night we all went to see ‘Gypsy.’ They wouldn’t let us in because we were black. We wrote the theater president and copied it to actor’s equity. We were told to ‘go slow’ and how we ‘can’t get in front of the masses.’ We told them the masses had no problem getting in the wrestling matches.

“And Sputnik got the masses involved.”

Memphis wrestling promoter Buddy Fuller put a rock n’ roll spin on Monroe. Elvis Presley’s “All Shook Up” and “(Let Me Be Your) Teddy Bear” were all over the charts in 1957 and Monroe’s pompadour created a Presley mystique. Fuller featured Monroe and his arch rival Billy Wicks on his 1959 WMC-TV television show. In 1959 Monroe and Wicks wrestled before 18,000 people at the outdoor Russwood Park in Memphis, where Lefty Gomez and Ernie Lombardi had toiled for the minor league Memphis Chicks. Retired heavyweight champion Rocky Marciano was guest referee. Monroe told friends that he and Wicks earned $500 each for the match while Marciano was paid $5,000 for his appearance.

Monroe had the wild white streak in his hair and he thought he was a sharp looking cat. Early in his career, Monroe got smacked in the head with a wooden chair during a match. An undetected splinter became infected. When the small piece of laminated wood was removed, the hair over the scar grew back in white. Over the years Monroe had his throat cut, shoulder stabbed, he was shot once in the ass and once on the leg with a pellet pistol. No one messed with his heart. At his peak, Monroe talked in a staccato rhythm that was a precursor to hip-hop. When former West Texas State football star Terry Funk made his wrestling debut, Monroe greeted him in the ring with the rap, “You little punk kid/I am going to whup your ass like Borden House pie/Cuz’ I’m a Diamond Ring and Cadillac Man/And am going to stay that way you little punk…..”

In 1958 John Dougherty was an East Memphis teenager who hung out with Jerry and Knox Phillips. Dougherty was founder and president of the Sputink Monroe Fan Club. Jerry Phillips was secretary. In 1961 Jerry Phillips, only 14, wrestled in small towns around Memphis as “De Layne Phillips: The World’s Most Perfectly Formed Midget Wrestler” and Dougherty played the role of his manager. Phillips and Dougherty had white blond streaks in their hair to honor their hero. Phillips was a heel like Monroe and his rival was a real midget named Fabulous Frankie Thumb. Dougherty had met Monroe through Sam Phillips. Known around Memphis as rock n’ roll disc jockey Johnny Dark, in 1980 Dougherty became program director of Phillips radio station WLVS-FM (named after Elvis).

“When Sputnik came to Memphis in 1957 they averaged about 300 people a night at the Ellis Auditorium,” Doughery said. “Within two months if you didn’t have a ticket in advance, you didn’t get in. Of course, he was the bad guy and everyone hated him because he stuck up for black people. Me and Jerry were the only whites cheering for Sputink. He would come out and not even look at the whites. Sputink would walk around the ring, look up to the balcony and raise both arms in the air. Every single black person in the balcony would jump up and put their arms in the air. I have emceed concerts by the Beatles, the Supremes, everybody who was big in the 1960s. He was the most charismatic person I ever met.”

“One time he went to the state fair and got into it with this cowboy at the rodeo. His intent was to meet Gene Barry (Bat Masterston of the cowboy televsion series). Sputink wanted to get in the barn with the Brahma Bull and the cowboy tried to stop him. They got into a fight and while Sputnink had his back turned, the cowboy hit him with a two-by-four. The next day on the front page of the Memphis Commercial-Appeal there was a picture of Sputink with some headline like ‘Cowboy Levels Wrestler.’ Down at the bottom there was a story about President Eisenhower’s heart trouble. Sputink was the lead story.” An active member of the NAACP and ACLU, Judge Sugarmon said Monroe was deeply respected in the black community. “They thought he was a guy who treated them like he treated everyone,” Sugarmon said. “He was a decent man.”

The outrageous marriage of rock n’ roll and wrestling made sense to Monroe, who left Memphis in 1960 for Lake Charles, La. “Both outlaws,” he grumbled. “That’s what the deal was. Elvis gave us music we never had before. And Sputnik did, too. Jerry Phillips and John (Dougherty) were always at the door to meet me when I left wrestling matches.” A plaque on the wall near the front door of in Monroe’s home read: “Sputnik Monroe, World’s Greatest Wrestler: Appreciation for your contribution to the City of Memphis, the world of wrestling and Memphis music. It’s all rock n’ roll to us. Memphis music friends and Wrestling Hall of Fame Celebration, Sam Phillips Recording Studios, Memphis, Tennessee—March 6, 1994.” A nearby framed certificate honored Monroe’s membership in “The Friendly Sons of Bitches.” It read, “Never forget, there’s the love of a girl for a boy and a love of a child for its mother. But the greatest love is the undying love is that of one son of a bitch for another.”

During the 1960s Monroe took on sons of bitches like Tokyo Tom in a wrestling circuit known as “The Amarillo Territory.” This is where Monroe he perfected his technique. “There’s probably 1,000 wrestling holds and 10,000 variations,” said Monroe, who is in the Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame in Schenectady, N.Y. “That’s hard for most people to understand.” He leaned over and clenched his fist. It was as tight as a promoter’s wallet. “They grab it and they’re in a lot of trouble,” he said as he looked at the fist. “Then they get a knee in the squash. You pick up moves by being put in a position you haven’t been put in before. You learn a hold and you catalog that. I wasn’t beat very often. I didn’t pay much attention as long as I was on top. Sometimes I got robbed by shady promoters like Buddy Fuller. He died wearing diapers and he didn’t know what planet he was on. That happens to all the bad guys. Eddie Graham committed suicide (in

1985 of a self-inflicted gunshot). Its unbelievable how those things happen to people who were short on the payoff.”

Monroe returned to Memphis now and then. He was there for the 2000 ribbon cutting of the Rock n’ Soul Museum. His final public appearance was in July, 2005 when he appeared at a legends bout at the DeSoto Civic Center in Mississippi, 10 miles south of Memphis. Monroe reprised his shtick with Billy Wicks. Dougherty escorted Monroe into the ring. He recalled, “Sputnik walked kind of slow, but he used to have this strut he would do when he got in the ring. The white people just hated it. And last July when the spotlight hit him and we walked out, I couldn’t believe that 76-year-old man was strutting. The crowd went crazy.” Monroe always loved the heat of the spotlight. He remembered, “I get kissed by people on Beale Street who didn’t see me wrestle. They heard from their parents or grandparents what I had done and thanked me for doing it. That’s pretty emotional, to have people walk up on the street and hug you and tell you ‘thank you’

for something you did 40 years ago.

“Its hell to see the toughest son of a bitch in the world cry when that happens.”

Monroe had a military funeral in front of 300 friends and family at Veterans National Cemetery in Pineville, La. Jerry Phillips was there. “The last few years had to be tough for him,” Phillips said. “The whole ‘falling from grace’ deal. When he was security guard, he’d get mad at some of the people he was trying to guard. He wanted to ‘strum ‘em in the head’ as he called it—-like a guitar. The end of his life didn’t work out like he thought it might, but that, too is a rock n’ roll story.”

Monroe’s last professional match was in 1998 at a small community center in Texas City, southeast of Houston. Around 500 people were in attendance. Few sights are as poignant as a 70-year-old wrestler with cauliflower ears and a wilted spirit. Monroe went into the ring with four herniated discs in his lower back and two in his neck. “The money man said I was a little slow,” Monroe reported in a whisper. “I said at that age, you got one year straight ahead—-slow.” Despite having lost half of his right lung to cancer and gangrene in his gallbladder, Monroe took another hit from a cigarette. “I’m not a quitter,” said the old wrestler, who poked at shadows cast from the Texas sun.

Leave a Response